In modern C++, efficient data handling is paramount, particularly in performance-critical applications where memory layout and access patterns can significantly impact overall performance. This post delves into the various methods of passing contiguous data buffers to functions in C++, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses. We’ll explore traditional approaches like raw pointers, std::vector, and std::array, before introducing std::span, a powerful C++20 feature designed to provide a safe, flexible, and type-safe alternative for managing contiguous memory. By understanding these approaches, developers can make informed decisions about data management in their applications, balancing safety, performance, and usability.

We will discuss the following topics in this post:

- Passing Contiguous Data Buffers in Performance-Critical C++

- Raw Pointers: The Decoupled Metadata Problem

- std::vector: Safe Size Handling but API Rigidity

- The std::array Type Rigidity Problem

- Template Solution: Risk of Binary Bloat

- std::span (C++20): A Non-Owning View for Contiguous Memory

- Limitation of std::span: No Container-Specific Operations

- Where Should We Use std::span in C++ Applications

- When NOT to Use std::span in C++: Common Pitfalls and Alternatives

- Conclusion

Passing Contiguous Data Buffers in Performance-Critical C++

When dealing with data, we often focus on contiguous memory layouts due to their cache efficiency and predictable access patterns. In performance-critical and systems-level C++ applications, this concern becomes central. In practice, there are only a few traditional ways to pass a data buffer to a function:

- raw pointers

std::vectorstd::array.

Each approach has architectural trade-offs that can lead to bugs, performance overhead, or rigid APIs if used indiscriminately.

Raw Pointers: The Decoupled Metadata Problem

The most primitive and historically common approach uses a raw pointer together with a separate size parameter. This pattern is still widely used in device drivers, networking stacks, and C APIs. The core issue here is that the metadata, specifically the buffer size, is not intrinsically bound to the data pointer. This separation creates a fragile contract that relies entirely on programmer discipline rather than compiler enforcement. Lets us have alook at the following example.

Example: Packet Processing Using a Raw Pointer Interface

// filename: sample_program_raw_pointer.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <cstdint>

void process_packet(const uint8_t* buffer, std::size_t length)

{

for (std::size_t i = 0; i < length; ++i)

{

std::cout << std::hex << static_cast<int>(buffer[i]) << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

int main()

{

uint8_t packet[] = {0xDE, 0xAD, 0xBE, 0xEF};

process_packet(packet, 4);

return 0;

}This program demonstrates the use of raw pointers in packet processing, a typical pattern in embedded systems, network programming, and performance-critical code. Network packets or protocol data often arrive in preallocated or fixed-size memory buffers, such as DMA-backed regions used in high-speed device drivers. These buffers pass through multiple parsing stages, where each stage may advance the pointer to skip headers while updating the remaining payload length.

If either the pointer advancement or length recalculation is incorrect, the function can end up reading beyond valid buffer boundaries. The compiler cannot detect such logical mismatches between pointer position and buffer size, and these errors often surface only under specific traffic patterns or timing conditions. The responsibility for maintaining consistency between the active pointer location and the buffer’s valid range rests entirely with the programmer, making this approach highly error-prone when compared to type-safe abstractions that apply compile-time or runtime bounds checking.

std::vector: Safe Size Handling but API Rigidity

The second option for buffer or data management that will come into mind is the use of std::vector. Using std::vector avoids the size mismatch problem because the container carries its size internally. From a correctness perspective, this is a significant improvement over raw pointers.

Example: Telemetry Logging with std::vector

// filename: sample_program_vector_telemetry.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

void log_telemetry(const std::vector<int>& entries)

{

for (int e : entries)

{

std::cout << e << " ";

}

std::cout << "\n";

}

int main()

{

std::vector<int> data = {10, 20, 30};

log_telemetry(data);

return 0;

}The limitation here is not safety. The function signature explicitly requires a std::vector. Therefore, the caller must already store the data in a vector. If the caller holds the data in a stack array, they cannot pass the buffer directly. The same applies to a memory-mapped buffer or a std::array. In practice, this often forces a conversion such as constructing a temporary std::vector and copying elements, even when the function only needs read-only access.

This is the key trade-off in the std::vector function interface: it couples the algorithm to a specific owning container. In low-latency or memory-constrained systems, heap allocation and copying can be a serious cost.

The std::array Type Rigidity Problem

The other choice for representing contiguous data would be std::array. Unlike raw arrays, it carries size information and integrates cleanly with the type system. For many embedded and performance-sensitive applications, these properties make std::array an excellent default container. But with std::array, the size of the buffer is part of the type itself. This means that two arrays with different sizes are treated as completely unrelated types by the compiler. Let us take a look at the following program.

Example: Size as Part of the Function Type

// filename: sample_program_array_rigid.cpp

#include <array>

#include <iostream>

void apply_filter(const std::array<float, 1024>& signal)

{

std::cout << "Processing 1024 samples\n";

}

int main()

{

std::array<float, 512> small_signal{};

std::array<float, 1024> large_signal{};

apply_filter(large_signal); // Works

// apply_filter(small_signal); // Compile-time error

return 0;

}This code fails to compile if small_signal is passed to apply_filter. The failure is not due to a logic error or a safety issue. It occurs because std::array<float, 512> and std::array<float, 1024> are different types, and the function explicitly accepts only one of them.

This rigidity is appropriate when the algorithm genuinely requires an exact number of elements. However, in many real-world algorithms, including signal processing, filtering, and numerical analysis, the logic does not depend on the size being a specific compile-time constant. It only depends on the data being contiguous and on knowing how many elements are available at runtime. At this point, developers often reach for templates.

Template Solution: Risk of Binary Bloat

Template on size N fixes compilation but generates separate machine code for each N. Let us have a look at the following example code.

Example: Templated std::array Interface

// filename: sample_program_array_template.cpp

#include <array>

#include <iostream>

template <std::size_t N>

void apply_filter(const std::array<float, N>& signal)

{

std::cout << "Processing " << N << " samples\n";

}

int main()

{

std::array<float, 512> small_signal{};

std::array<float, 1024> large_signal{};

apply_filter(small_signal); // Instantiates apply_filter<512>

apply_filter(large_signal); // Instantiates apply_filter<1024>

return 0;

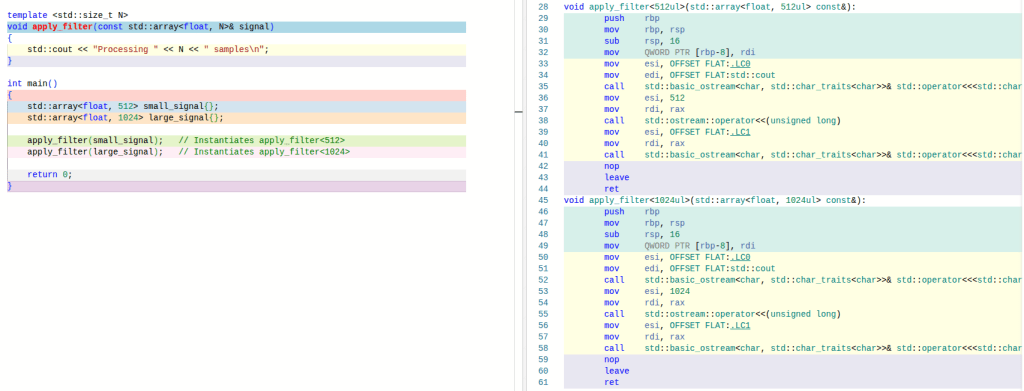

}This version compiles and works correctly. Each call generates a separate instantiation of the function for the corresponding size. The algorithmic logic is identical, but the compiler emits distinct machine code for each value of N. You can verify this here: https://godbolt.org/

Figure: Separate template instantiations for each array size

This behavior is expected and correct, but it has practical consequences. As the number of supported sizes grows, so does the number of generated functions. This increases binary size, symbol count, and compilation time.

Now here comes our friend std::span to rescue us from the above situations. Let us have a look how it works.

std::span (C++20): A Non-Owning View for Contiguous Memory

C++20 introduces std::span, which is designed specifically for passing and processing contiguous buffers in function interfaces, including the situations discussed so far. Before using it, it helps to be clear about what std::span is and what it is not.

std::spanis not a containerstd::spandoes not own memory and never performs allocation or deallocation.std::spanis a lightweight view over an existing contiguous block of memory, such as a C-style array, astd::array, astd::vector, or a raw pointer paired with a length.

The key idea is that std::span provides access to elements and the number of elements, without taking responsibility for how that memory is created, resized, or freed.

How std::span Encapsulates Pointer and Size

Internally, a span is typically implemented as a pointer to the first element and a size. The canonical form is std::span, with a dynamic extent by default.

A span acquires its size as follows:

- From a C-style array, the size is deduced at compile time.

- From a

std::vector, the size is obtained fromvector::size(). - From a

std::array, the size is part of the array’s type. - From a raw pointer, the size must be supplied explicitly.

C++ std::span: Writing Type‑Safe, Container‑Independent Functions for Contiguous Data

std::span in C++20 offers a type-safe, non-owning view for passing arrays, std::vector, std::array, and other contiguous sequences to functions. It enables bounds-checked access with a bundled pointer and size, enhancing safety while maintaining performance in modern interfaces. Lets us take a look at how it works in the next example.

Example: Universal Sensor Data Processing with std::span

// filename: sample_program_with_span.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <span>

#include <vector>

#include <array>

void process_sensors(std::span<const int> data)

{

std::cout << "Processing " << data.size() << " elements: ";

for (int val : data)

{

std::cout << val << ' ';

}

std::cout << '\n';

}

int main()

{

// 1. C-style array (size deduced automatically)

int raw_array[] = {1, 2, 3};

process_sensors(raw_array);

// 2. std::vector (size taken from container metadata)

std::vector<int> v = {10, 20, 30, 40};

process_sensors(v);

// 3. std::array (size taken from type)

std::array<int, 2> a = {100, 200};

process_sensors(a);

// 4. Subview created from a container

process_sensors(std::span(v).subspan(1, 2));

// 5. Raw pointer with explicit size

int sensor_buffer[] = {7, 8, 9, 10, 11};

int* ptr = sensor_buffer + 1; // pointer to second element

std::size_t count = 3; // number of valid elements

process_sensors(std::span(ptr, count));

return 0;

}Compile and Run the Program

To compile the program issue the following command in the Linux console:

g++ --std=c++20 sample_program_with_span.cpp -o sample_program_with_span -Werror -WallAnd to run the program do the following:

$ ./sample_program_with_span

Processing 3 elements: 1 2 3

Processing 4 elements: 10 20 30 40

Processing 2 elements: 100 200

Processing 2 elements: 20 30

Processing 3 elements: 8 9 10 You can see how std::span can be used to write generic functions to accept any contiguous data source such as a raw array, std::vector, or std::array through a single, consistent interface. This example shows all supported ways of constructing a std::span in a realistic function interface.

- When passing a C-style array, the span deduces the size automatically.

- When passing a

std::vector, the span usesvector::size(). - When passing a

std::array, the size comes from the array’s type. - When passing a raw pointer, the size must be supplied explicitly.

The last case is particularly important in systems code. Legacy APIs, memory-mapped regions, DMA buffers, and driver interfaces often provide a pointer and a length, not a container. Constructing a std::span from that pointer and length binds the two together immediately, after which the function operates on a single object instead of two loosely related parameters.

Once the span is constructed, the function no longer deals with a pointer and a separate size. It works with a bounds-aware view that can be sliced, iterated, and passed further without risking pointer–size mismatches.

Limitation of std::span: No Container-Specific Operations

However, std::span is not a magic wand in all situations. You will soon realise that the moment you pass data as a std::span, you are choosing a buffer view, not a container interface. That means container-specific operations are no longer available. std::span does not support memory management or container utilities. It cannot resize, allocate, or manage storage. Methods such as push_back, insert, erase, reserve, and capacity are not available.

Where Should We Use std::span in C++ Applications

std::span should be used wherever a function needs to access contiguous data but does not need to own or manage that data. This follows directly from its design. std::span is a non-owning view of contiguous memory, not a container. Its responsibility is limited to accessing and iterating over an existing block of elements, while ownership, allocation, and lifetime management remain with the original source, such as a raw buffer, std::vector, or std::array.

This makes std::span particularly suitable for algorithmic and processing code, where the logic operates on data but should not control how that data is stored.

When NOT to Use std::span in C++: Common Pitfalls and Alternatives

std::span provides a lightweight, non-owning view over contiguous data in C++20, ideal for function parameters. However, using std::span as class members, for lifetime management, non-contiguous data, or container-specific ops leads to bugs like dangling references.

Avoid std::span as Class Data Members

Storing std::span in classes risks dangling pointers when source data is destroyed or reallocated, causing undefined behavior in C++ applications. Prefer std::vector or std::array for ownership in long-lived objects. This prevents subtle crashes common in embedded systems or multithreaded code.

Skip std::span for Lifetime Management

std::span cannot extend data lifetime, making it unsafe for queues, caches, or async tasks outliving the source buffer. Use owning types like std::unique_ptr<std::vector<T>> or std::shared_ptr for persistence.

std::span Fails with Non-Contiguous Containers

std::span requires contiguous memory, incompatible with std::list, std::forward_list, or deque tails. Switch to iterators, std::ranges, or container views for scattered data access.

No Container-Specific Methods in std::span

std::span lacks container-specific methods such as vector::reserve(), capacity(), array::fill(), or push_back(). If your interface is relies on container specific methods then std::span won’t help.

Conclusion

C++20 introduces a tool that can help you write cleaner, more robust, and safety critical code in the form of std::span. Whether it makes sense to use it or not depends on your specific use case, and that decision should take into account the trade-offs discussed in this post.

std::span is not a replacement for existing containers or memory management techniques. Instead, it acts as a facilitator for safer and clearer interface design, helping to address several long standing issues when working with non owning views over memory in C++.

If you would like to receive more posts like this in your inbox, please subscribe.

Except std::span is not zero-cost on microsoft abi.

https://developercommunity.visualstudio.com/t/std::span-is-not-zero-cost-because-of-th/1429284

LikeLike

Thank you for pointing that out. Most of my experience has been on the embedded Linux side, so I was not fully aware of this MSVC ABI-related limitation. I appreciate the clarification and the link.

LikeLike