Sometimes, you may need to invoke a Linux command from your C++ program and capture its output. Once you have the output, the next step might be to parse it and take some meaningful action based on the results. Fortunately, Linux provides a handy system function called popen, which makes this task much easier.

Today, I’m going to take a deep dive into the popen function, exploring how it works and how we can leverage it to execute Linux commands directly from a C++ program. We’ll see how to capture the command’s output, process it, and even print it to the console. By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of how popen can be used effectively to interact with the Linux shell from within a C++ application.

Object modelling

Because it is C++ I will take an Object oriented approach which to model the program around C++ classes and structures. To start with let’s call our C++ program SystemAnalyser. Our SystemAnalyser class will have the below functionalities:

- Able to launch a Linux command

- Able to capture the output of the command

- Able to display the command on the console.

The above functionalities are quite simple and will good to start with. These are fairly simple operations and we will implement these with simple C++ class methods. So lets design the class.

#ifndef __SYSTEM_ANALYSER_H__

#define __SYSTEM_ANALYSER_H__

#include <string>

class SystemAnalyser

{

public:

SystemAnalyser();

virtual void RunCommand(const char * command);

virtual void StoreOutput(std::string& result);

virtual void DisplayOutput();

virtual ~SystemAnalyser();

};

#endif

The above is our blueprint for the SystemAnalyser class from the information we have will now. This I have declared in .h file and the plan is to have the implementation in a .cpp file later. Our skeleton cpp file looks like this at this point:

#include "SystemAnalyser.h"

SystemAnalyser::SystemAnalyser()

{

}

void SystemAnalyser::RunCommand(const char * command)

{

}

void SystemAnalyser::StoreOutput(std::string& result)

{

}

void SystemAnalyser::DisplayOutput()

{

}

SystemAnalyser::~SystemAnalyser()

{

}

Now we are going to write a short main.cpp and try to compile the code in a Linux prompt.

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

#include "SystemAnalyser.h"

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World" << std::endl;

auto system = std::make_unique<SystemAnalyser>();

system->RunCommand("ls -la");

system->DisplayOutput();

return 0;

}

Compile the skeleton

I am not going to write a makefile at this point as it would be a bit of overkill. So let’s try compile the above code from command line:

~/system_analysier/SystemAnalyser$ g++ --std=c++17 main.cpp SystemAnalyser.cpp -o system

~/system_analysier/SystemAnalyser$ ./system

Hello World

So at this point the program is not doing much except printing hello world and reasonably so because we have not really implemented anything. Now lets extend the RunCommand method to get it doing the real work.

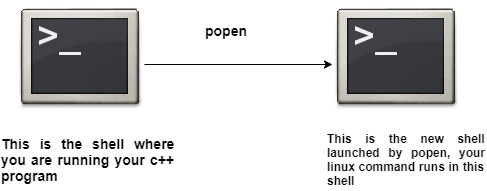

We are going to use the Linux system function called popen for launching our command. You can have a read about what this functions do from the Linux man page. I will try to briefly discuss what these functions does in the following two paragraph.

Popen()

In a nutshell popen function does the following operations:

- creates a pipe stream

- creates a new process by fork()

- invokes the Linux shell /bin/sh

The pipe popen creates is unidirectional. This essentially means either you can read it, or you can write into it, but not both. You can imagine a pipe as a new stream of data. You either generate data by writing into the pipe or receive data by reading from it. Popen takes a command string which is what we want to invoke in the shell. We need to be clear that with popen, we invoke a new shell. After that, we execute our command.

Implementation

Now with that brief background on popen() lets try implement our RunCommand() method. I will first show you a sample implementation and then try explaining it step by step. Here is the implementation:

std::string SystemAnalyser::RunCommand(const char * command)

{

std::array<char, 128> buffer;

std::string result;

std::unique_ptr<FILE, decltype(&pclose)> pipe(popen(command, "r"), pclose);

if (!pipe) {

throw std::runtime_error("popen() failed!");

}

while (fgets(buffer.data(), buffer.size(), pipe.get()) != nullptr) {

result += buffer.data();

}

std::cout << result << std::endl;

return result;

}

In the above code snippet, we are opening a pipe with the popen() function. We are collecting the pipe descriptor, which popen returns, in a pointer named pipe. This is just a name. Instead of pipe, you can also name the pipe descriptor as your first name or anything you like. Lets focus on the below line and try to understand what it is doing:

std::unique_ptr<FILE, decltype(&pclose)> pipe(popen(command, "r"), pclose);

In the above line of code we are using C++ smart pointer, unique_ptr() for holding the pipe descriptor as pipe descriptor is nothing but a pointer itself. The interesting part creating this unique_ptr is that we are passing a deleter as well and its type. A deleter is something which the C++ runtime uses to destroy the memory created by popen when the pointer goes out of scope. There are really two parts to understand in how the unique_ptr is being created as below:

- specifying the type of the deleter

- specifying the deleter

A deleter in this case is nothing but a function called pclose(). Pclose is a Linux system provided function. What we are telling the C++ compiler in the below code is that use the type of the deleter as been declared in the library:

std::unique_ptr<FILE, decltype(&pclose)>That’s precisely what decltype does. It tells the compiler to consider the type of an object to be the same as a previously specified type. In this case, the compiler knows the type of the system function pclose(). This is because it has been included from the library. Now coming to specifying the deleter function. We are specifying the name of the library function pclose() here:

pipe(popen(command, "r"), pclose)I am not going to explain the rest of the part of the smart pointer. That is not the focus here. So lets move on to the next part which is how to capture the output from the pipe.

To capture the output from the pipe we simply need to read the pipe using the pipe file descriptor. So first thing we need to check if we have a valid pipe descriptor, we do that as below:

if (!pipe) {

throw std::runtime_error("popen() failed!");

}

As you can see, we are checking if the pipe pointer is holding a non-zero value. If it is not, then this is not a valid pointer. We are throwing an exception with the error message.

We need a buffer to hold our output, so we are declaring a buffer here using C++ array data type.

std::array<char, 128> buffer;It doesn’t have to be strictly an C++ type array, it could be a simple C type array for this purpose. But this is a C++ implementation so I used more C++ types than C.

To read from the pipe we use a Linux function called fgets(). This is the way we are reading the data from the pipe stream:

while (fgets(buffer.data(), buffer.size(), pipe.get()) != nullptr) {

result += buffer.data();

}

What we are telling the fget() is where to put the read data. Buffer.data() gives the raw pointer to the first element in the array. Remember our array is named ‘buffer.’ Then, we specify how many bytes to read, buffer.size(), which is 128 bytes maximum. So with one fgets() call we can read maximum 128 bytes.

Now, lets look at the below line:

pipe.get()If you are familiar with smart pointers in C++, you know that unique_ptr() is a manged pointer, hence it is not the actual raw pointer. So to get the actual pointer from the unique_ptr we need to use an accessor function called get(). The above line returns the underlying pointer. This pointer is our pipe descriptor required for reading from the pipe.

We are using a while loop. If there is more data than just 128 bytes in the pipe, fget will return a string. The loop will keep running and reading more data from it until it becomes empty. fget() will then encounter EOF and return a null pointer. At that point, the loop will stop.

In each loop we keep appending the string read into a string type named ‘result’ in our implementation. At the end of the while loop the RunCommand function returns the complete string read from the pipe. We can store this string in a class member string type, lets call it outputStore and declare it in the private section of the SystemAnalyser class as below:

private:

std::string outputStore; Now, our StoreOutput() function can contribute something significant. It does this by taking the result string as input. Then, it assigns this input to the class member string outputStore. Obviously, not very path breaking but useful for explaining the concept here. So our StoreOutput() function looks like this now:

void SystemAnalyser::StoreOutput(std::string result)

{

outputStore = result;

}

StoreOutput() is called within the RunCommand() class member function and hence it doesn’t have to be public. I would ideally move it to the private section of the class. I want to avoid giving any unnecessary member function access to the end user. Therefore, my intention is to make as many functions and variables private as possible. That is an OOP approach you may consider in your program as well.

Now, coming to the displaying the result part. It is very simple. Now, our StoreOutput() function has stored the output in a class member string. The display function just has to pass it to the cout object. That should be it. This is what we can do:

void SystemAnalyser::DisplayOutput()

{

std::cout << outputStore << std::endl;

}

And finally this is how our friend RunCommand() and StoreOutput() functions looking like:

void SystemAnalyser::RunCommand(const char * command)

{

std::array<char, 128> buffer;

std::string result;

std::unique_ptr<FILE, decltype(&pclose)> pipe(popen(command, "r"), pclose);

if (!pipe) {

throw std::runtime_error("popen() failed!");

}

while (fgets(buffer.data(), buffer.size(), pipe.get()) != nullptr) {

result += buffer.data();

}

StoreOutput(result);

}

void SystemAnalyser::StoreOutput(std::string result)

{

outputStore = result;

}

If you notice, I have changed the return type of the RunCommand function from std::string to void. After storing the output as a string in the class member outputStore, there is no need to return the output.

So that is pretty much it. The source code can be downloaded from here.

Finally, a sample output of the above program should look like below:

VBR09@mercury:~/system_analysier/SystemAnalyser$ ./system

Hello World

total 64

drwxr-xr-x 2 VBR09 tpl_sky_pdd_jira_user 4096 Dec 23 18:51 .

drwxr-xr-x 4 VBR09 tpl_sky_pdd_jira_user 4096 Dec 23 14:20 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 VBR09 tpl_sky_pdd_jira_user 683 Dec 23 18:51 SystemAnalyser.cpp

-rw-r--r-- 1 VBR09 tpl_sky_pdd_jira_user 329 Dec 23 18:49 SystemAnalyser.h

-rw-r--r-- 1 VBR09 tpl_sky_pdd_jira_user 244 Dec 23 14:22 main.cpp

-rwxr-xr-x 1 VBR09 tpl_sky_pdd_jira_user 44608 Dec 23 18:51 system

In the next blog, we will expand the functionalities. We will include an output parser. This will offer a better look at the interesting bits of the output.

Till then, bye!

thanks, it helps me a lot to have a knowledge on C++ and shell

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike