In multi-threaded C++ environments, the primary concern remains protecting shared resources from concurrent access. Developers typically reach for std::mutex and std::lock_guard or other C++ RAII lock variants to achieve this. However, as C++ system complexity grows, it becomes clear that no “one-size-fits-all” C++ locking policy exists. Different C++ concurrency scenarios demand distinct synchronization designs, an aspect modern C++ multithreading often overlooks.

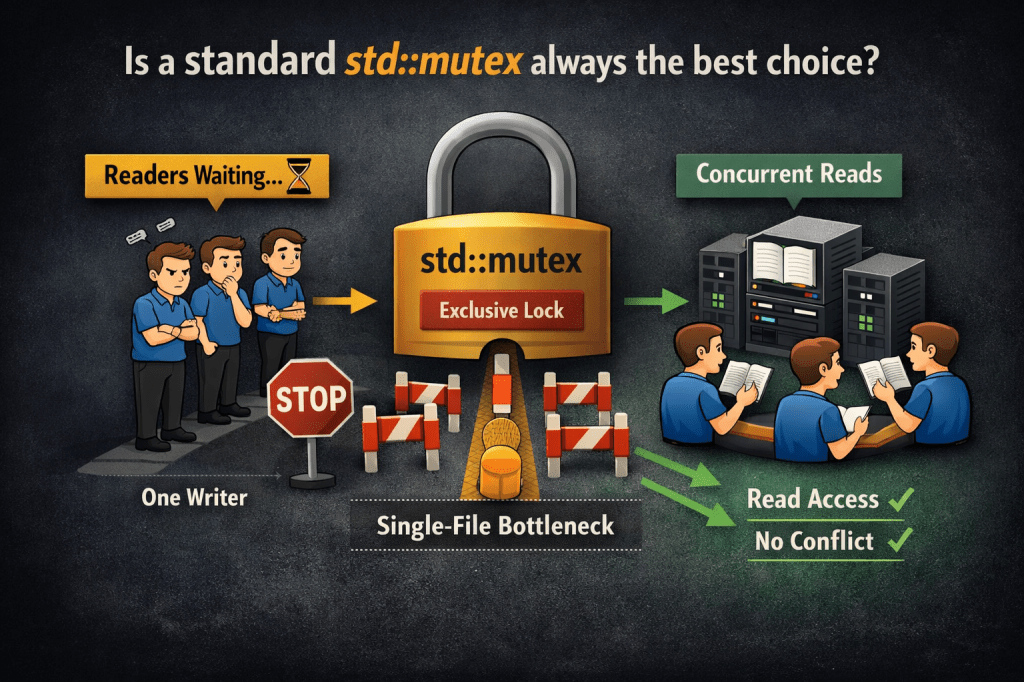

Is std::mutex always the best choice in C++ multithreading? Consider a classic C++ reader-writer scenario where multiple threads need to read shared data, but only one thread writes to it. Developers often default to a standard std::mutex for protection in this kind of scenario.

However, readers pose no threat to shared data since they access it without modification. Forcing readers to wait behind an exclusive std::mutex lock means only one reader accesses the data at a time, even though reading doesn’t alter shared state.

This C++ mutex serialization turns potentially parallel read operations into strictly sequential processing, creating an unnecessary concurrency bottleneck in read-heavy workloads.

The only time C++ truly demands exclusive locking is when a writer enters the critical section. For these C++ reader-writer scenarios, C++ offers a specialized read-write mutex called std::shared_mutex that supports both shared reader access and exclusive writer access.

std::shared_mutex is designed for read-heavy C++ multithreaded workloads with many concurrent readers and few writers, where using std::mutex would serialise read access, reduce parallelism, and waste available CPU cores on modern multi-core systems. The performance advantages aren’t immediately obvious, so we’ll use Google Benchmark C++ to measure std::mutex vs std::shared_mutex scaling and reveal how these read-write locks behave under real multi-threaded C++ workloads.

In this post we will discuss the following topics:

- Installing Google Benchmark on Ubuntu

- Designing the GoogleBenchmark Test Code

- Benchmark Test Environment

- Performance Comparison: std::mutex vs std::shared_mutex Benchmarks

- Addendum: Multiple Readers with Lighter Read Workloads

- What to Keep in Mind

- Source Code

Installing Google Benchmark on Ubuntu

Before we dive into the code, the benchmark library must be installed on your system. On Ubuntu, you can set this up using the following commands:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install libbenchmark-dev libgtest-dev cmake g++Designing the GoogleBenchmark Test Code

We will design the test step by step to compare a standard mutex against a shared mutex.

Defining the Data Context

We encapsulate the shared data and the mutexes into a single structure. To ensure the most accurate results, we use alignas(64). This prevents “False Sharing,” where the hardware cache coherency protocol causes performance degradation because two different mutexes happen to reside on the same CPU cache line.

struct BenchmarkContext {

std::map<int, double> data;

// Mutexes are separated by 64 bytes to avoid cache line contention

alignas(64) std::mutex regular_mtx;

alignas(64) std::shared_mutex shared_mtx;

void setup() {

if (data.empty()) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

data[i] = std::sqrt(i);

}

}

}

};

static BenchmarkContext g_ctx;Simulating the Workload

We require a “Heavy Read” to make the test realistic. If the work inside the lock is too small, the benchmark will only measure the overhead of the lock mechanism itself. By performing trigonometric calculations, we simulate actual data processing.

void DoHeavyRead() {

double total = 0;

// Performing math operations forces the CPU to spend time inside the lock

for (int i = 0; i < 50; ++i) {

total += std::sin(g_ctx.data[i % 1000]);

}

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(total);

}benchmark::DoNotOptimize(total) prevents compiler over-optimization from discarding our heavy read workload, ensuring Google Benchmark captures true C++ lock contention timing.

The Comparison Logic

In our Google Benchmark tests, we use state.thread_index() to identify each thread’s unique index. Thread index zero becomes the writer, while all remaining threads act as concurrent readers.

- Regular Mutex: Every thread uses

std::lock_guard, which is always exclusive. - Shared Mutex: The Writer uses

std::unique_lock(exclusive), while Readers usestd::shared_lock(shared).

// Logic inside the loop for Shared Mutex

if (state.thread_index() == 0) {

std::unique_lock<std::shared_mutex> lock(g_ctx.shared_mtx);

DoWrite(); // Exclusive access

} else {

std::shared_lock<std::shared_mutex> lock(g_ctx.shared_mtx);

DoHeavyRead(); // Parallel access

}The Write Simulation

The writer’s responsibility remains modifying shared state under exclusive access to guarantee concurrency correctness in multithreaded environments. In our benchmark, this critical role lives in a small, focused write function:

void DoWrite()

{

g_ctx.data[0] += 1.1;

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(g_ctx.data[0]);

}This writer function performs a single shared data update, incrementing the first element of g_ctx.data. The operation stays intentionally simple: we’re isolating synchronization overhead in std::shared_mutex benchmarks.

Under std::unique_lock, this execution blocks all concurrent readers temporarily, both active and pending.

Complete Code Listing

The following program implements the logic discussed above using the Google Benchmark framework.

Example: A Performance Comparison of Exclusive vs. Shared Locking.

/**

* @file shared_mutex_vs_mutex_bench.cpp

* @brief Performance comparison between std::mutex and std::shared_mutex.

*/

#include <benchmark/benchmark.h>

#include <cmath>

#include <map>

#include <mutex>

#include <shared_mutex>

#include <vector>

struct BenchmarkContext {

std::map<int, double> data;

alignas(64) std::mutex regular_mtx;

alignas(64) std::shared_mutex shared_mtx;

void setup() {

if (data.empty()) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

data[i] = std::sqrt(i);

}

}

}

};

static BenchmarkContext g_ctx;

void DoHeavyRead() {

double total = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < 50; ++i) {

total += std::sin(g_ctx.data[i % 1000]);

}

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(total);

}

/**

* @brief Simulates a writer modifying shared state.

*/

void DoWrite() {

g_ctx.data[0] += 1.1;

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(g_ctx.data[0]);

}

static void BM_RegularMutex_Mixed(benchmark::State &state) {

g_ctx.setup();

for (auto _ : state) {

// All threads—readers and writers—must wait for exclusive access.

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(g_ctx.regular_mtx);

if (state.thread_index() == 0) {

DoWrite();

} else {

DoHeavyRead();

}

}

}

BENCHMARK(BM_RegularMutex_Mixed)->ThreadRange(2, 8)->UseRealTime();

static void BM_SharedMutex_Mixed(benchmark::State &state) {

g_ctx.setup();

for (auto _ : state) {

if (state.thread_index() == 0) {

// Writer acquires exclusive access, pausing all readers.

std::unique_lock<std::shared_mutex> lock(g_ctx.shared_mtx);

DoWrite();

} else {

// Readers acquire shared access, allowing parallel execution.

std::shared_lock<std::shared_mutex> lock(g_ctx.shared_mtx);

DoHeavyRead();

}

}

}

BENCHMARK(BM_SharedMutex_Mixed)->ThreadRange(2, 8)->UseRealTime();

BENCHMARK_MAIN();Compiling and Running the Program

To compile the code, we use the -O3 optimization flag and link the benchmark and pthread libraries.

g++ -O3 shared_mutex_vs_mutex_bench.cpp -o lock_bench -lbenchmark -lpthread

./lock_benchBenchmark Test Environment

Tested on 8-thread Intel i7-3770 @ 3.40GHz (4 cores, 8 threads with HT) running Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS (Linux 6.8.0 kernel). All std::mutex vs std::shared_mutex benchmarks executed with g++ -O3, ThreadRange(2,8), and UseRealTime() for wall-clock accuracy.

Key Hardware Factors

- 8 logical cores via Hyper-Threading on 4 physical cores

- 8MB L3 cache per core impacts lock contention patterns

- 64-byte cache line alignment (alignas(64)) prevents false sharing

- PREEMPT_DYNAMIC kernel minimizes scheduling variability

Performance Comparison: std::mutex vs std::shared_mutex Benchmarks

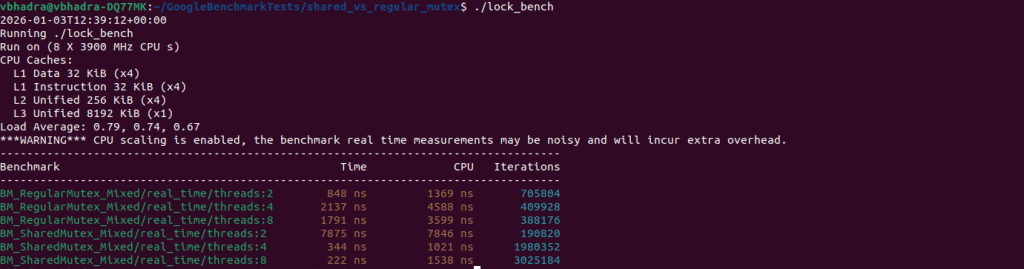

When the test binary is executed, Google Benchmark provides a detailed breakdown of the performance metrics. Below is a sample run from a machine with an 8-core CPU.

Understanding the Columns

Here is what the headers in this output represent:

- Benchmark: The name of the test followed by the thread count. For example,

threads:8means 1 writer and 7 readers were active. - Time (Real Time): This is the “Wall Clock” time. It is the most important metric for multi-threaded apps as it measures how long the task actually took from start to finish, including time spent waiting for locks.

- CPU: This measures the total CPU time consumed. In multi-threaded tests, this is often higher than Real Time because it sums the work done across all active cores.

- Iterations: The number of times the framework ran the loop to get a statistically stable average.

Analysis of BM_RegularMutex_Mixed (std::mutex)

Now, let us we explore the performance of std::mutex in a multi-threaded C++ program where one writer thread updates shared data and multiple reader threads access it concurrently. Understanding this behaviour is essential for developers looking to optimise C++ concurrency and multi-threaded read performance. The table below shows benchmark results from Google Benchmark for different numbers of threads:

| Thread | Real Time (ns) | CPU (ns) |

| 2 | 848 | 1369 |

| 4 | 2137 | 4588 |

| 8 | 1791 | 3599 |

std::mutex shows increased contention as threads grow, limiting read throughput.The Real Time column measures wall-clock time per iteration, including time spent waiting for the mutex. With 2 threads, Real Time is 848 nanoseconds. In this case, contention is minimal because only one reader shares access with the writer, and the mutex enforces exclusive access.

When the thread count increases to 4, Real Time rises sharply to 2137 nanoseconds. This reflects the serialized nature of std::mutex. Every thread, whether reading or writing, must wait its turn. As more threads compete, thread contention increases, reducing the efficiency of multi-threaded reads.

At 8 threads, Real Time drops slightly to 1791 nanoseconds. This minor variation is within the expected statistical margin of multi-threaded benchmarking and does not indicate improved performance.

The CPU Time column indicates the total CPU cycles consumed across all threads.

Analysis of BM_SharedMutex_Mixed (std::shared_mutex)

Now, let us examine how std::shared_mutex performs under a mixed workload consisting of one writer and multiple readers, as measured using Google Benchmark and compared against std::mutex.

The following table presents the performance statistics observed for std::shared_mutex during the benchmark run.

| Thread | Real Time (ns) | CPU (ns) |

| 2 | 7875 | 7846 |

| 4 | 344 | 1021 |

| 8 | 222 | 1538 |

From the benchmark results, it is clear that with two threads std::shared_mutex records a Real Time of 7875 nanoseconds, which is significantly higher than the 848 nanoseconds observed with std::mutex. This behaviour is expected in a low-concurrency configuration where there is only one reader and one writer. In such a case, access to the shared data is effectively serialized, and the shared mutex is unable to exploit its core advantage of concurrent reads.

Unlike std::mutex, std::shared_mutex must maintain additional internal state to distinguish between shared and exclusive ownership and to manage transitions between them. When the number of readers is small, this extra bookkeeping cost is not amortised and directly increases the cost of lock acquisition and release, resulting in higher observed latency.

As the number of threads increases, this trade-off changes. With four threads, the Real Time drops sharply as multiple readers are now able to acquire the shared lock concurrently whenever the writer releases it. This behaviour follows directly from the use of std::shared_lock in the code and reflects the scenario for which std::shared_mutex is designed. With eight threads, the effect becomes more pronounced, as several reader threads execute the read workload in parallel, allowing the system to make effective use of available CPU cores.

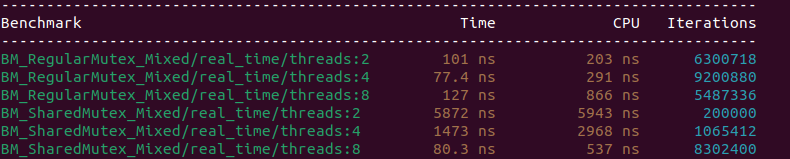

Addendum: Multiple Readers with Lighter Read Workloads

The situation may change if the read-side critical section is much lighter. To test this case, I added the following code and ran the benchmark again:

Light Read Source Code for testing

The only change here is that the read workload is comparatively lighter as below:

/**

* @brief EXTREMELY LIGHT Read Workload.

* Perform a single lookup instead of 50 trig calculations.

*/

void DoLightRead()

{

double value = g_ctx.data[500];

benchmark::DoNotOptimize(value);

}With this code in place we can run the test again and see the following output:

Lets compare these in a side by side view as the below:

| Threads | std::mutex (Real Time) | std::shared_mutex (Real Time) | Observations |

| 2 | 101 ns | 5872 ns | shared_mutex much slower |

| 4 | 77.4 ns | 1473 ns | shared_mutex much slower |

| 8 | 127 ns | 80.3 ns | shared_mutex faster |

| 16 | 131 ns | 86.0 ns | shared_mutex faster |

The above table shows test results from a much lighter read but increased number of threads. You can see that with extremely light read-side critical sections, std::shared_mutex performs worse. This happens because std::mutex at low thread counts suffers from higher locking overhead. As thread count increases, the dominant cost becomes exclusive locking in std::mutex. A crossover reappears. In this scenario, std::shared_mutex scales better by allowing concurrent readers.

What to Keep in Mind

- There is no single best mutex for all situations. The right choice depends entirely on how your data is accessed in a multi-threaded environment.

std::shared_mutexis designed to benefit read-heavy workloads, where many threads frequently read shared data and write operations are relatively rare.- The performance advantage of

std::shared_mutexappears only when there are enough reader threads to take advantage of concurrent access. - With few readers, shared locking provides little or no benefit and can perform worse than a regular mutex due to its additional management overhead.

std::mutexremains a strong and efficient choice for low concurrency scenarios or write-heavy designs, where exclusive access is unavoidable anyway.- As reader concurrency increases, exclusive locking becomes a bottleneck, while shared locking allows the system to make better use of available CPU cores.

- The key to good concurrency design is understanding your workload, especially the balance between reads and writes, rather than assuming that a more advanced synchronization primitive will always be faster.

- Measuring and observing real behaviour, even with simple benchmarks, leads to better design decisions than relying on assumptions or defaults.

Source Code

All the source code for the benchmark programs discussed in this article is available in the following GitHub repository.

1 Comment