In Chapter 1 : Introduction to Templates in C++, we briefly encountered function templates in C++. In this chapter, we focus on how to implement a C++ function template in a clear and systematic manner. Throughout this book, the terms “template function” and “function template” are used interchangeably. For all practical purposes, there is no distinction between the two. Function templates in C++ form the foundation of generic programming, enabling the creation of reusable algorithms that operate independently of specific data types. At first glance, the syntax of a C++ function template can appear unfamiliar and somewhat intricate. For this reason, we will approach the topic incrementally, breaking down the structure and syntax of a function template step by step to develop a precise and intuitive understanding.

By the end of this chapter, you will understand the general syntax of a C++ function template, learn how to apply that syntax, and define your own function templates correctly. You will also gain clarity on how the C++ compiler processes a function template in two distinct stages. The chapter then examines automatic function template instantiation performed by the compiler, including both explicit and implicit instantiation. Finally, we discuss how defining a function template within a separate namespace helps avoid name conflicts with other templates, whether from the Standard Template Library or the global namespace.

In this chapter we will learn the following topics:

- Syntax of a function template

- Writing a function template

- Two-phase compilation

- Function template instantiation

- Explicit Specification of Template Argument Types

- Summary

- Source Code

Syntax of a function template

Let’s have a look at the syntax of a single parameter function template:

template

Template-return-type template-name(T argument-name)

{

…

Template body

…

}A C++ function template declaration begins with the keyword template. This is immediately followed by an opening angle bracket, which marks the start of the template parameter declaration. The keyword typename appears next, followed by the name of the template parameter. The template parameter name can be any valid identifier. However, T has historically been a widely used and conventionally accepted name for a template parameter in C++ code.

A function template definition can have either a single template parameter or multiple template parameters. Once all template parameters are declared, the parameter list is closed using the closing angle bracket. The keyword class can also be used in place of typename. There is no semantic difference between the two in this context. However, typename is often preferred, as it more clearly conveys the intent of declaring a type parameter rather than a class specifically.

The template parameter T behaves like any built in or user defined data type within the function template body. Once introduced, it can be used in the same manner as a concrete type. Specifically, T can be used in the following ways:

- To specify the return type of the function template

- To specify the type of one or more function parameters

- Within the function template body to declare variables, just as you would with any built in or user defined data type

In the next section, we will apply this syntax and the concepts discussed so far to write our first C++ function template.

Writing a function template

Now that know the syntax of a function template, let us write our first function template as follows:

#include <iostream>

template<typename T>

T abs(T myvar)

{

return myvar > 0 ? myvar : (-myvar);

}

int main()

{

double dVar = -20.5;

std::cout << abs(dVar) << std::endl;

int iVar = 10;

std::cout << abs<>(iVar) << std::endl;

char cVar = 'A';

std::cout << abs(cVar) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

In this example, we define a C++ function template named abs. The function template declaration begins with the keyword template, followed by an opening angle bracket that introduces the template parameter list. Inside the angle brackets, the keyword typename is used to declare the template parameter T, and the list is then closed with a closing angle bracket. The template parameter T represents the type of the function argument myvar. The same template parameter T is also used as the return type of the function template, ensuring that the function returns a value of the same type as its input.

Inside the function body, a conditional expression is used to return the absolute value of myvar. The expression evaluates whether myvar is greater than zero and returns either the original value or its negation accordingly.

In the main function, the abs function template is invoked with arguments of different types. First, a negative value of type double is passed using the variable dVar. Next, a positive value of type int is passed using iVar, where the empty angle brackets explicitly indicate template usage, although the template argument is still deduced by the compiler. Finally, a value of type char stored in cVar is passed to the same function template. In each case, the compiler generates the appropriate function instance based on the argument type. If you compile and run the program, the corresponding absolute values are produced as output.

$ g++ abs.cpp -o abs -Wall -Werror

$ ./abs

20.5

10

A

Note:

We have added a few additional compiler flags while compiling this program. These flags are useful during development, as they help identify potential programming issues that could otherwise lead to unintended bugs.

-Wallenables a broad set of compiler warnings during compilation. These warnings highlight potential problems in the code but do not stop the compilation process.-Werrortreats all compiler warnings as errors and terminates the compilation if any warning is encountered. Using this flag enforces stricter code quality and is recommended for future compilations once the codebase stabilises.

When a function template is invoked with specific arguments, the compiler deduces the argument types and binds them to the template parameter T. Based on this deduction, the compiler then generates a concrete instance of the function template by substituting T with the deduced type. In the next section, we examine this compiler processing of function templates in greater detail.

Two-phase compilation

The C++ compiler processes a function template in two distinct phases. The exact behaviour can vary slightly across different compilers, but the underlying concept remains consistent.

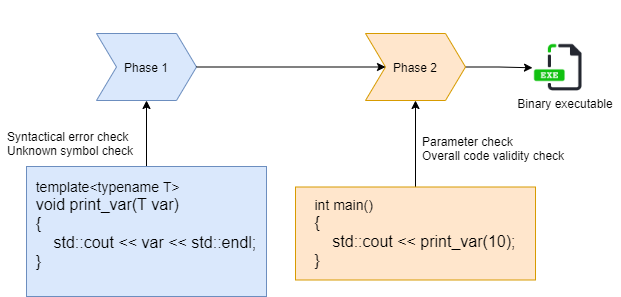

First Phase of Lookup

During the first phase of lookup, the compiler examines the function template definition for syntactic correctness and unresolved symbols. At this stage, the compiler does not validate template parameters or perform full semantic checks related to the template arguments.

Second Phase of Lookup

In the second phase, which occurs when the function template is invoked within the program, the compiler verifies the template parameters and evaluates the overall validity of the instantiated template code. If any mismatch in template arguments is detected, or if other programmatic inconsistencies are found, the compiler reports an error. The following diagram illustrates these two lookup phases involved in function template processing.

Let us now examine the following code example to understand this behavior more clearly.

Example: First Phase Lookup

#include <iostream>

struct foo_struct {

int a;

};

template<typename T>

void foo(T& mystruct)

{

std::cout << "a = " << mystruct.c << std::endl

}

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

This program defines a structure named foo_struct, which contains a single member variable a of type int. In the definition of the function template foo, two errors have been introduced deliberately. First, the statement inside the template function body is missing a terminating semicolon. Second, the code attempts to access a member variable c of the foo_struct data type. However, no such member exists. As a result, when you compile this program, the compiler reports the following error.

two_phase_lookup.cpp: In function 'void foo(T&)':

two_phase_lookup.cpp:11:1: error: expected ';' before '}' token

Notice, the compiler reports only the missing semicolon error, which corresponds to the first issue in the function template definition. A missing semicolon is a syntactic error, and such errors are detected immediately when the compiler parses the template definition.

However, the compiler does not report the second issue, namely the access to a non existent member variable, because the function template foo is never invoked from main. Since the template is not instantiated, the compiler does not perform full validation of template dependent expressions. As a result, the second error is not diagnosed at this stage.

To proceed further, we first correct the missing semicolon in the body of the foo function template, as shown below.

void foo(T& mystruct)

{

std::cout << "a = " << mystruct.c << std::endl;

}

After correcting the missing semicolon, the program recompiles without any errors. This happens because the function template foo is still not invoked anywhere in the program. Since the template function is not called, the compiler does not enter the second phase of lookup.

Example: Second Phase Lookup

To force the compiler to perform the second phase of template processing, the function template foo must be invoked from within main. Calling the function template enforces instantiation, which causes the compiler to fully validate the template dependent code. To achieve this, we modify the main function in the previous program to include a call to foo, as shown next.

#include <iostream>

struct foo_struct {

int a;

};

template<typename T>

void foo(T& mystruct)

{

std::cout << "a = " << mystruct.c << std::endl;

}

int main()

{

foo_struct mystruct{10};

foo(mystruct);

return 0;

}

If you compile the program, you will see the following compilation error:

$ g++ two_phase_lookup.cpp -Wall -Werror -o two_phase_lookup

two_phase_lookup.cpp: In instantiation of 'void foo(T&) [with T = foo_struct]':

two_phase_lookup.cpp:16:17: required from here

two_phase_lookup.cpp:10:37: error: 'struct foo_struct' has no member named 'c'

std::cout << "a = " << mystruct.c << std::endl;

The function template foo is now called with an object of type foo_struct. Therefore, the compiler attempts to instantiate the template using foo_struct as the template argument. During this second phase of compilation, the compiler fully validates the template dependent code. At this stage, it detects that foo_struct does not contain a member named c, which results in a compilation error. To resolve this error, you must correct the invalid member access. Replace the non existent member c with the valid member a, as shown below.

template<typename T>

void foo(T& mystruct)

{

std::cout << "a = " << mystruct.a << std::endl;

}

The second phase of template compilation is directly associated with template instantiation. We will explore template instantiation in more detail in the next section.

Function template instantiation

In Chapter 1, Introduction to Templates in C++, we examined a conceptual model of function template instantiation. In this section, we build on that foundation. We explore the mechanism in greater detail. We focus on how and when the compiler generates different instances of a function template for various data types. There are two distinct ways in which function templates can be instantiated, which we will discuss in the following sections.

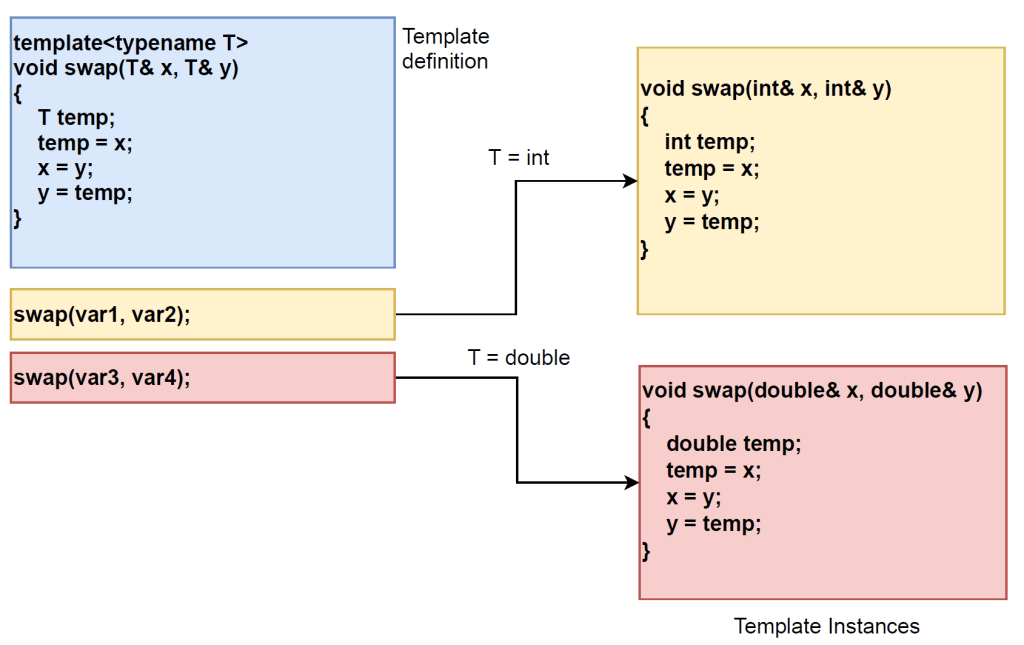

Implicit instantiation

Whenever a function template is invoked with a set of data types that differs from all previous invocations, the compiler implicitly generates a new instance of the template using the actual data type supplied as the argument. This process is known as template instantiation, or more specifically, implicit instantiation. Let us now examine the following example to understand this behaviour more clearly.

#include <iostream>

template<typename T>

void swap(T& x, T& y)

{

T temp;

temp = x;

x = y;

y = temp;

}

int main()

{

int var1 = 10, var2 = 20;

std::cout << "Before: var1 = " << var1 << " var2 = " << var2 << std::endl;

swap(var1, var2);

std::cout << "After: var1 = " << var1 << " var2 = " << var2 << std::endl;

double var3 = 40.5, var4 = 20.5;

std::cout << "Before: var3 = " << var3 << " var4 = " << var4 << std::endl;

swap(var3, var4);

std::cout << "After: var3 = " << var3 << " var4 = " << var4 << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Compile the program using the following command:

$ g++ template_instance_swap.cpp -o template_instance_swap -Wall -WerrorIn this program, we define a function template that accepts two arguments of type T and swaps their values. In the main function, the template function swap is invoked twice. First, it is used with two variables of type int. Then, it is used with two variables of type double. As discussed earlier, the compiler implicitly generates separate instances of the function template swap for each distinct data type used. In this case, one instance is generated for int and another for double. The following diagram provides a pictorial representation of this template instantiation process performed by the compiler.

Examining Compiler Generated Template Instances Using nm

To examine the compiler generated instances, we will use the tool nm in Linux command line as follows:

$ nm -C template_instance_swap | grep -i swap

0000000000000c51 W void swap<double>(double&, double&)

0000000000000c24 W void swap<int>(int&, int&)

The nm tool lists all the symbols present in the input binary. The -C option converts low level, compiler generated symbol names into readable, user level function names. In our case, we list the symbols present in the template_instance_swap executable. We then filter the output to search for the string swap. The output confirms that the compiler has generated two distinct instances of the template function. One is for the type int, and the other is for the type double. The symbol for swap<int> appears at address 0000000000000c24. The symbol for swap<double> appears at address 0000000000000c51 in the generated binary.

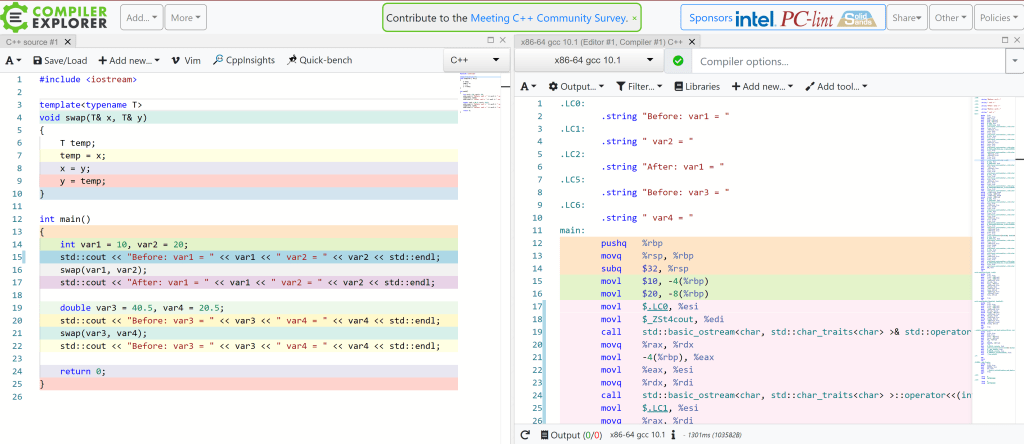

Inspecting Compiler Generated Code Using Compiler Explorer

If you want to examine the compiler generated code in more detail, you can use the online Compiler Explorer (https://godbolt.org/). Copy or upload your C plus plus source file into the left pane of the explorer. Then select an appropriate compiler such as x86-64 gcc version 10.1. Finally, compile the code. The right-hand pane then displays the output produced by the compiler. To copy and paste our current program, first place it into the left pane. Ensure the compiler is set to x86-64 gcc version 10.1. Then the generated output appears as shown in the following image.

In the right-hand pane of the explorer, locate the main() function. Within main(), you will see the call to the swap() function template, as shown below.

call void swap<int>(int&, int&)

call void swap<double>(double&, double&)

This confirms that the compiler has correctly deduced the argument types. Further down in the right-hand pane, you can observe the instantiated definitions. Two function template instances are displayed, as shown below.

void swap<int>(int&, int&):

void swap<double>(double&, double&):

To generate assembly code offline, you can use the -S option with the g++ compiler, as shown below.

$ g++ template_instance_swap.cpp -SThis will generate an output file called 📎 template_instance_swap.s as shown below:

$ ls -la template_instance_swap.s

-rw-r--r-- 1 VBR09 tpl_sky_pdd_jira_user 6280 Aug 20 14:42 template_instance_swap.s

The file template_instance_swap.s contains the assembly code generated by the compiler. You can open this file to examine the compiler generated assembly version of the function template swap(). You can also search for the template function name directly. Do this from the command line within the assembly file, as shown below.

$ cat template_instance_swap.s | grep -i swapThe output of this command will be cluttered with lots of assembly symbols. The most interesting are the following two lines:

_ZN11mynamespace4swapIiEEvRT_S2_:

…

_ZN11mynamespace4swapIdEEvRT_S2_:

This is how the swap() function template name appears in the generated assembly code. Such names are referred to as mangled names. In simple terms, the C++ compiler modifies function and identifier names so that the linker can uniquely distinguish them from other symbols. To obtain a human readable name corresponding to the mangled symbol shown above, you can use the following tool.

$ c++filt _ZN11mynamespace4swapIiEEvRT_S2_

void mynamespace::swap<int>(int&, int&)

$ c++filt _ZN11mynamespace4swapIdEEvRT_S2_

void mynamespace::swap<double>(double&, double&)

Now different compiler-generated versions of the swap() function can be seen in a more human-readable way.

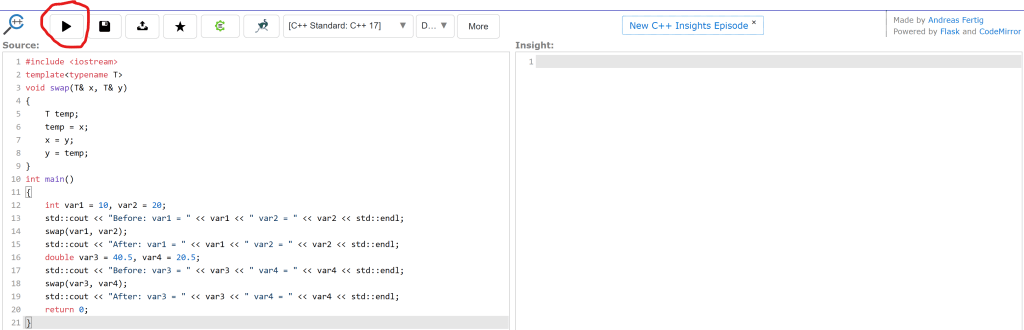

Examining Template Instantiation Using cppinsights.io

One other way you can examine the template instantiation is using the https://cppinsights.io/. This is a great resource. If you go to this site, you will see something like the following:

On the left-hand side pane, you can write your cpp code. Alternatively, you can copy the example code and paste it in the left-hand side pane as shown in the following diagram:

Once you have copied the example code and pasted it into the left-hand pane, as shown in Figure 2.6, locate the Run button in the upper-left corner of the page. The Run button appears as illustrated in Figure 2.6. You can also select the compiler you wish to use. For this example, C++ 11 has been selected. After clicking the Run button, the instantiated versions of the function template swap() are displayed in the right-hand pane. This display is similar to what is shown below.

As shown in Figure 2.7, the compiler has instantiated two different versions of the swap() function template. One uses the int type. The other uses the double type. This provides another way to examine the code generated by the compiler for our function template. The observation is consistent with what we have seen earlier using other tools. In this program, the compiler has therefore implicitly generated two distinct instances of the function template. However, it is also possible to explicitly instruct the compiler to instantiate a function template. In the next section, we will examine how to do that.

Explicit instantiation

In explicit instantiation of function templates, we instruct the compiler to create an instance of the template function. This happens at a specific point. This is done instead of waiting for the function template to be invoked elsewhere in the program. Let us examine this concept using the following example. We will first look at the corresponding header file.

#ifndef __H_EXPLICIT_INST__

#define __H_EXPLICIT_INST__

#include <iostream>

template<typename T>

T add(T x, T y)

{

return x + y;

}

template int add<int>(int x, int y);

#endifIn the header file explicit_instantiation.h, we define a function template named add(), and then explicitly instantiate the add() function template as shown below.

template int add<int>(int x, int y);The above statement instructs the compiler to instantiate the function template with the data type int. The compiler performs this instantiation as soon as it encounters the instruction. There is no need to wait for the function template to be invoked elsewhere in the program. This behaviour can be verified using the following verification code.

📎 verify_explicit_instantiation.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "explicit_instantiation.h"

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Notice that in the verify_explicit_instantiation.cpp file, we have included the header file explicit_instantiation.h, but the template function add() is not invoked anywhere in the program. The header file contains an explicit instantiation directive for the data type int. Therefore, the compiler must generate an instance of the template function. This occurs even though the template function is never called within the program. Let us now compile the code and verify that the add() function template has indeed been instantiated, as shown below.

g++ verify_explicit_instantiation.cpp -o verify_explicit_instantiation

$ nm -C verify_explicit_instantiation | grep -i "add"

000000000000094b W int add<int>(int, int)

The executable binary generated for the program verify_explicit_instantiation contains an instance of the function template add(). This instance is instantiated with the data type int. This confirms that the compiler has generated binary code for the template function add() even though the function is never invoked anywhere in the program. This behaviour is a direct result of the explicit instantiation directive present in the header file, as discussed earlier.

To further validate this behaviour, comment out the following statement from the explicit_instantiation.h header file.

template int add<int>(int x, int y);And then, compile the program and search for the add() symbol using the nm tool as was shown in the following:

$ g++ verify_explicit_instantiation.cpp -o verify_explicit_instantiation

$ nm -C verify_explicit_instantiation | grep -i "add"

As shown above, no instance of the add() function template is present in the generated executable. This is because the template function is neither invoked within the program nor explicitly instantiated in the header file. We have verified the behavior of explicit instantiation. We have also checked the corresponding binary code generation. Now, we proceed to examine how the add() function template is used within a CPP file, as shown next.

To comprehend the usage of an explicitly instantiated function template across multiple translation units, we examine a simple example. It involves two source CPP files. The intent here is to demonstrate that the template function add() can be used from different source files. This is possible once it has been explicitly instantiated in the header.

The source file, explicit_instantiation_1.cpp, acts as the program entry point. Its purpose is to demonstrate that the explicitly instantiated template function add() can be called directly from main(). Then, execution can be delegated to another function defined in a separate source file.

📎 explicit_instantiation_1.cpp

#include<iostream>

#include "explicit_instantiation.h"

void foo();

int main()

{

std::cout << add(10, 20) << std::endl;

foo();

return 0;

}

The source file, explicit_instantiation_2.cpp, demonstrates that the same explicitly instantiated template function add() can be used from a separate translation unit. The function foo() is defined within this source file and invokes add() independently. It relies on the template instance that the compiler has already generated through explicit instantiation. This approach avoids triggering a new instantiation.

📎 explicit_instantiation_2.cpp

#include "explicit_instantiation.h"

void foo()

{

std::cout << add(30, 50) << std::endl;

}

In explicit_instantiation_2.cpp, we call the add() function template from within the function foo(). In explicit_instantiation_1.cpp, the main() function first calls the add() function template directly, and then invokes foo(), which in turn calls add() again from a different translation unit. This setup allows us to observe how an explicitly instantiated template function is reused across multiple source files without triggering additional instantiations. You can now compile the program as follows:

g++ explicit_instantiation_1.cpp explicit_instantiation_2.cpp -o explicit_instantiation -Wall -WerrorThe compiler first compiles both CPP files independently. The linker then resolves the symbols across translation units. It produces the final binary executable named explicit_instantiation. Explicit instantiation reduces some flexibility provided by function templates. The instantiated types are fixed explicitly by the programmer. However, in certain scenarios this trade off can be useful. This is particularly true when tighter control over template instantiation and binary generation is required. In practice, explicit instantiation is used sparingly, and therefore we will not explore it in greater depth here. It is sufficient to understand that explicit instantiation is supported by the language and can be applied when such control is necessary. In the next section, we will see how to explicitly specify template arguments when invoking function templates.

Explicit Specification of Template Argument Types

So far, we have observed the compiler automatically deduce the template arguments. It then uses the deduced types for function template instantiation. However, at times we may need to explicitly promote the type of a template argument to enforce a specific operation. In the following sections, we will see how this can be achieved.

Explicit Type Promotion in Function Templates

Let us say you have defined a template function to compare two numbers. It has a single template parameter of type T, and two function arguments, both of type T. Now, for certain programming requirements, let us say you have an int and a double. You want to use the same function template and compare the int with the double. This may be required when promoting the int to double does not affect the correctness of the comparison.

If you pass an int and a double directly to the template function, the compiler will report a type mismatch. This occurs during parameter checking. The template expects both arguments to be of the same type. So how do you achieve this? Let us have a look at the following code snippet.

#include <iostream>

#include <typeinfo>

namespace mynamespace {

template<typename T>

T is_equal(const T& x, const T& y) {

std::cout << "type of x = " << typeid(x).name() << std::endl;

std::cout << "type of y = " << typeid(y).name() << std::endl;

return x == y;

}

}

int main()

{

int var1 = 10;

double var2 = 20.0;

if(!mynamespace::is_equal<double>(var1, var2)) {

std::cout << var1 << " " << var2 << " are not equal" << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

In this program, var1 is of type int and var2 is of type double. You want to compare var1 and var2 even though they are of different types. You are certain that promoting var1 from int to double is acceptable for the current programming requirements.

To achieve this, you can explicitly specify the template argument type when calling the function template. In this scenario, you specify the template argument as double. You do this by writing it inside the angle brackets immediately after the function name. This forces the compiler to instantiate the template with T as double, and both arguments are treated as double within the function body, as shown in the call:

if(!mynamespace::is_equal<double>(var1, var2)) {As a result, var1 is implicitly converted to double. The comparison is then performed between two values of the same type. To check the type promotion of var1 from int to double, we used typeid. This allowed us to print the types of x and y inside the template function. Since the template is explicitly instantiated with double, both parameters are treated as double within the function body. If you compile and run the program, you will see the following output:

$ g++ type_promotion.cpp -o type_promotion -Wall -Werror

$ ./type_promotion

type of x = d

type of y = d

10 20 are not equal

The typeid operator returns the type information of an expression as known at runtime. In this example, x and y are not polymorphic types. Thus, typeid reflects the static type from template instantiation rather than dynamic dispatch. Notice that the type of var1 is reported as d. This corresponds to double according to the typeid operator, as seen in the program output. This confirms that var1 was promoted from int to double when the template was explicitly instantiated with double.

To further verify that the compiler generated code for the template function using the double type, follow the steps below. You can use the nm tool we introduced earlier.

$ nm -C type_promotion | grep -i is_equal

0000000000000b85 W double mynamespace::is_equal<double>(double const&, double const&)

As you can see, the compiler has instantiated the is_equal() function template. It used the template argument double. This is indicated by the symbol name shown in the output. This confirms that explicitly specifying the template argument forces the compiler to generate the corresponding template instance. This occurs even when the original arguments are of mixed types.

There is one more situation in which explicit template argument specification becomes necessary. We will discuss this in the next section.

Explicit Template Argument Specification When Deduction Is Not Possible

Usually, the compiler is smart enough to deduce the types of template arguments from the function template call itself. However, there are situations where the required types are not evident from the template function call alone. In such cases, template argument deduction fails, and the type must be specified explicitly. Let us examine the following example.

#include <iostream>

#include <string.h>

const int max_size = 32;

template<typename T>

T* my_alloc_factory()

{

return new T[max_size];

}

int main()

{

char *myPtr = my_alloc_factory();

strncpy(myPtr, "Hello World", max_size);

std::cout << myPtr << std::endl;

delete[] myPtr;

return 0;

}

In this example, we have defined a function template. It allocates an array of elements of type T with a fixed size max_size in memory. The template returns the address of the allocated memory as a pointer of type T to the caller. The function template is invoked from main() using the following statement:

char *myPtr = my_alloc_factory();The intention here is to allocate a memory area of size max_size for elements of type char. An array of char elements represents a character buffer. When it is null terminated, it is commonly treated as a C style string. Now, if you try to compile the program, you will see errors similar to the following:

explicit_argument.cpp: In function 'int main()':

explicit_argument.cpp:12:36: error: no matching function for call to 'my_alloc_factory()'

explicit_argument.cpp:5:4: note: candidate: template<class T> T* my_alloc_factory()

explicit_argument.cpp:5:4: note: template argument deduction/substitution failed:

explicit_argument.cpp:12:36: note: couldn't deduce template parameter 'T'The compiler is indicating a failure. It could not deduce the template argument type required for instantiation from the template function call itself. Since no function arguments are passed, the compiler has no basis for template argument deduction.

Resolving the Deduction Failure Using Explicit Specification

To resolve this issue, you must explicitly specify the template argument type using angle brackets, as shown below:

char *myPtr = my_alloc_factory<char>();As you can see, we specified the type char explicitly. This will tell the compiler that it is dealing with char type here and there will be no compilation error.

In the next section, we are going to learn how the name of a template function can have a conflict. This conflict can occur with the names of template functions available in STL. It can also occur with the names of any previously defined template functions in the global namespace. We will also discuss the solution to it.

Summary

- Function templates enable type-independent functions without code duplication.

- A function template is not executable code until it is instantiated.

- The C++ compiler processes function templates using two-phase compilation:

- Phase one checks syntax and symbol validity.

- Phase two performs type checking during instantiation.

- Template errors may appear only when the template is used, not when it is defined.

- The compiler generates a separate function instance for each distinct template type.

- Function template instantiation can be:

- Implicit, triggered by a function call.

- Explicit, forced by a programmer instruction.

- Explicit instantiation causes the compiler to generate code even if the template is never called.

- Template argument deduction works only when types can be inferred from function parameters.

- When deduction is not possible, explicit template argument specification is mandatory.

- Explicit template argument specification can also be used to control type promotion.

- Template functions may conflict with standard library templates if names overlap.

- Namespaces and scope resolution are required to avoid template name ambiguity.

- Understanding function templates is essential before learning class templates, as the core concepts are shared.

Source Code

All the source code for the sample programs shown in this chapter is available in the following GitHub repository.

3 Comments