Welcome to the world of C++ Templates, a powerful but lesser-used feature of the C++ language, which can significantly improve developing clean code in any large or small-scale project. A template is essentially a design of a function or a class using generic data type. It empowers the programmer to write generic code which can work with different data types. This chapter will introduce you to the concept of templates with a brief history to understand where it all started. This chapter will act as the foundation for future chapters and take you gradually to the deeper details about templates.

This chapter is organized a follows.

- Brief history of templates

- What Is a Template in C++

- Advantages of Using Templates

- Templates Compared with Function Overloading

- Macro versus templates

- Important facts about templates

- Summary

- Source Code

Brief history of templates

The concept of templates is not new in C++. The consideration to incorporate templates as a feature started in the early ’80s. The first formal proposal for templates came in the mid-’80s. The feature was implemented in the year 1991. Since then, the templates have evolved continuously and become a significant part of the C++ programming paradigm. In the following year (1992), some additional features were added: template instantiation and member template.

Alongside, works were ongoing to develop a standard library since the late ’70s. In 1998, Standard Template Library (STL) was first incorporated into the language. Almost everything in STL is written in templates. Later, C++11 brought in some significant new features such as variadic templates and alias templates. C++14 introduced new features such as variable templates and generic lambdas (related to templates). Then C++17 further introduced features such as “Compile-time if” and Class template argument deduction. With this basic information of templates’ evolution, let us understand the importance of templates in C++ programming in the next section.

What Is a Template in C++

Templates are the way to generic programming. What does that mean? For example, let‘s say you want to find a minimum of two numbers. To achieve this, what are the different things coming into your mind? You might possibly be thinking about the following list of things at this point:

- That you will accomplish this by writing a function that takes two numbers as input.

- The types of the data for the two input numbers

- The internal logic to determine the minimum of the two numbers.

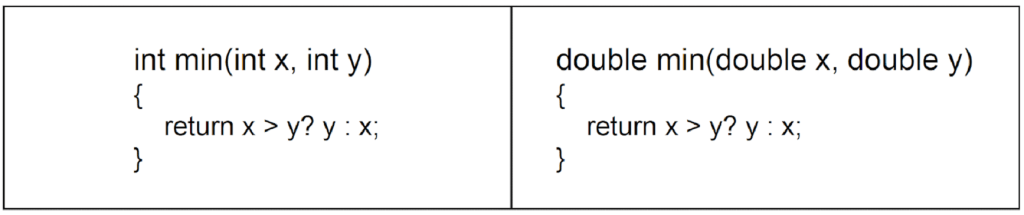

If the data types of the input numbers change, you must rewrite the same function. It needs to accommodate the new data types. If there are three different types of data you need to work with (e.g. int, double, char), you need to write three different versions of the same function which is not a very elegant solution.

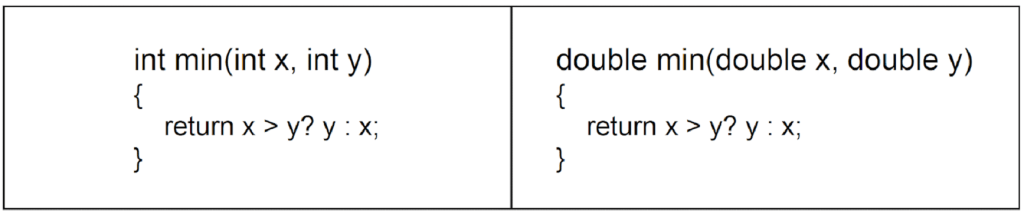

Let’s say you have written a function that returns a minimum of two integers. Now you realize you have to do the same for two doubles. You need to write a function that would return a minimum of two doubles. The internal logic of these two versions of the functions is identical, but the input data type is different. The possible implementation of the same could be as follows:

The two versions of the min() function we implemented perform the same task. However, they use different data types, namely int and double. This creates redundant code. We can avoid this by using a single, flexible function that works with multiple data types.

This is where generic programming in C++ comes in. It allows programmers to define functions or classes with generic data types. This enables the compiler to determine the appropriate type based on the arguments passed. Essentially, the programmer instructs the compiler:

This function should work with different data types. I’ll specify a generic type in the definition. The compiler will decide which specific type to use based on function calls.

By leveraging C++ templates, developers can write reusable, scalable, and type-safe code, eliminating redundancy while improving maintainability. In the next section, we will explore how to implement a generic version of the min() function using templates.

Template example from STL

Now, coming back to our minimum of two numbers problem. First, we will see how we can write a program using a generic function available in STL. The STL provides a function called std::min(). It takes two input numbers of any type. It returns the minimum of the two. Let’s have a look at the following code snippet:

#include <iostream>

#include <algorithm>

int main()

{

int min_of_two = std::min(100, 200);

std::cout <<"Min of 100 and 200 is " << min_of_two << std::endl;

return 0;

}

The output of this program will look as follows:

Min of 100 and 200 is 100.The STL library function std::min() takes a pair of integers. As you can see, it returns the minimum of those two. But what’s so special about that? To understand that, let’s expand our program as follows:

#include <iostream>

#include <algorithm>

int main()

{

int min_of_int = std::min(100, 200);

std::cout << "Min of 100 and 200 is " << min_of_int << std::endl;

double min_of_double = std::min(4.5, 2.3);

std::cout << "Min of 4.5 and 2.3 is " << min_of_double << std::endl;

return 0;

}

The general syntax for compiling a C plus plus source file using the GNU compiler is:

g++ <program-name>.cpp -o <output executable name>In this case the command will be as shown below:

g++ min_numbers.cpp -o min_numbersHere the name of the CPP file we are compiling is min_numbers.cpp and the name of the output executable is min_numbers. The name of the output file can be anything you like. if you do not specify an output filename then by default Linux names the binary executable as a.out. So, if you compile it with the following command then you will have an a.out file in the same directory:

$ g++ min_numbers.cpp -o min_numbers

$ ./a.outThe extension of the output file really doesn’t matter. Name it as you like, either keep or skip the extension if you like; Linux doesn’t care. To run the program, type the following command in the Linux console and press the Enter button:

./min_numbersOutput:

Min of 100 and 200 is 100

Min of 4.5 and 2.3 is 2.3We have modified the code in the second C++ file. We did this by adding another call to the same std::min function. This time, the function is called with two values of type double instead of int. Apart from this change, the structure of the program remains the same. From the output, it is evident that the very same function works correctly for both integer and floating point values, without requiring any separate implementation. This behavior highlights an important feature of the STL. The function std::min is a template function provided by the standard library and is defined in the algorithm header. It is not tied to a specific data type. Instead, it can operate on different types as long as they support comparison. Such functions are called generic functions. The C++ language feature that makes this possible is called templates.

Looking at a sample template

To give you a flavour of templates, we will now convert our own min() function into a template function. Let us see how such an implementation might look. One possible implementation of the min() function using templates is shown below:

template<typename T>

T min(T x, T y)

{

return x > y ? y : x;

}Please ignore the implementation details of the template function for now. We will discuss them in detail in the coming chapters. The key point to notice here is that this single implementation of the min() function works for multiple data types. These types include int, double, and char. Without templates, you would need to write separate functions for each of these types. By using templates, you avoid repeating the same source code multiple times. This example provides an initial idea. It shows how templates reduce code redundancy. Templates also make programs more flexible and reusable.

Advantages of Using Templates

By this point, you should have a reasonable sense of how using templates in C++ and the Standard Template Library (STL) can help reduce redundancy in source code. In this section we will discuss how we can benefit from using templates in our code.

Readability, Maintainability, and Long Term Code Health

In any project, maintainability is a significant concern. The challenge involves not only writing code that works today. It also includes ensuring that the code remains easy to understand, modify, and extend over the years. Code readability plays a crucial role in achieving this goal. Clearer code is easier to reason about. It is also easier to review and maintain over time.

Templates and Readability

Templates can significantly improve readability by reducing redundant code. Source code typically goes through a long life cycle. During this cycle, one set of programmers may write it. Another set of programmers often maintains it. The programmers who originally write the code are not always the ones who later debug or extend it. Readability, therefore, refers to how easily someone who did not write the code can understand it by simply reading it. Templates promote generic and compact code, which in turn improves readability and makes the codebase easier to maintain.

Code Redundancy and Reliability

Less redundant code generally results in a smaller and more manageable codebase. An increase in the number of lines of code also increases the likelihood of defects. Each additional line introduces another opportunity for error. Templates help in writing more reliable code by reducing mistakes that arise from manual duplication of similar logic. The compiler can automatically generate multiple versions for various functions or classes. It does this for different data types based on a single template definition. This automation significantly reduces the chances of accidental inconsistencies and human errors. As a result, using templates leads to cleaner, more reliable, and easier-to-maintain source code. As we progress through the chapters, we will see that templates offer more than improved readability. They also improve maintainability. These benefits strongly motivate us to begin using them.

Problems with Code Repetition

Source code repetition is not advisable due to several practical issues.

Writing repeated code is time consuming and inefficient. Writing the same logic in multiple places is tedious. It can also be error prone. The programmer may inadvertently introduce defects while rewriting similar code. Such errors are often the result of simple human mistakes rather than flawed logic.

When code is repeated, software maintenance becomes a serious concern. Every time a bug is fixed in one place, the same fix must be applied everywhere that code appears. This overhead increases significantly in large projects.

Example: Multi-Platform Maintenance Challenges

Imagine you have written three versions of a function. These are foo(int, int), foo(double, double), and foo(char, char). Each version performs the same task for different data types.

Now assume that the organization maintains three different platforms, where a platform refers to the underlying hardware. For example, one platform may use a Broadcom chipset, the second an STMicroelectronics chipset, and the third a Samsung chipset. Each platform maintains a separate codebase, typically managed as separate version control branches. If a bug is discovered in foo(int, int) and corrected, you must manually replicate the fix if the same issue applies to the other two versions. This needs to be done across all three functions.

This results in three changes per platform. Since there are three platforms, a total of nine changes must be made to apply a single fix consistently. Porting, in this context, refers to replicating the same change across all relevant platforms and codebases. By contrast, using a single template-based implementation means that the same correction would require only one change per platform. This reduces the total number of changes from nine to three. This reduction represents a substantial improvement, especially in large codebases consisting of millions of lines of code. By a fix, we mean a modification to the source code that resolves a specific defect or incorrect behaviour.

Type Safety and Compile Time Checking with Templates

The compiler performs strict type checking when a template function is invoked. Template argument deduction ensures that the types of the passed arguments are validated at compile time. At this stage, it is not necessary to focus on the syntax or internal mechanics of templates. We will revisit these concepts in the next chapter. The purpose of this section is to highlight one practical benefit of using templates, namely stronger type safety.

The Problem with Implicit Type Conversion

Consider the following example.

#include <iostream>

int add(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << add(10, 20) << std::endl;

std::cout << add(10, 20.2) << std::endl;

return 0;

}Compile the code as follows:

g++ type_conversion.cpp -o type_conversion

Run it using the following code:

./type_conversion

The output will be as follows:

30

30

In this program, we have defined a function add() that takes two integers and returns their sum. In the main() function, we first pass a pair of integers to the add() function. Then, we deliberately pass an integer and a double in the second function call. The function returns a result for both calls, producing 30 in each case. The second result is incorrect, as adding 10 and 20.2 should produce 30.2. Alternatively, one might expect the compiler to reject the second function call. This is because the argument types do not match the function definition. However, the compiler does not report an error, and the program produces an unexpected result.

This behaviour occurs due to automatic type conversion performed by the compiler. When the argument types do not exactly match the parameter types, the compiler applies a set of implicit conversion rules. In this case, the compiler converts the double value to an int so that it matches the function signature. While such conversions are permitted, they can easily lead to subtle and unintended errors. The detailed rules governing implicit conversions are outside the scope of this book.

How Templates Enforce Stronger Type Safety

Now, let’s convert our add() function into a template function as follows:

🔗 type_conversion_template_simple.cpp

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

T add(T x, T y)

{

return x + y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << add(10, 20) << std::endl;

return 0;

}Compile and run the code. You will see the output is 30:

30

Now let’s change the code to replace the second argument to add() to a double as follows:

🔗 type_conversion_template.cpp

#include <iostream>

template <typename T>

T add(T x, T y)

{

return x + y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << add(10, 20.5) << std::endl;

return 0;

}If you attempt to compile this program, the compilation will fail. The compiler produces an error similar to the following:

$ g++ type_conversion_template.cpp -o type_conversion_template

type_conversion_template.cpp: In function 'int main()':

type_conversion_template.cpp:10:30: error: no matching function for call to 'add(int, double)'This error indicates that the compiler tried to deduce the template parameter type from the function call. It found conflicting types in its attempt. Template argument deduction does not allow implicit type conversion. As a result, the compiler correctly rejects the call at compile time.

This behavior is beneficial to the programmer. An incorrect function call is detected early, during compilation, rather than leading to unexpected behavior at runtime. This stronger type checking is one of the important advantages of using templates. It helps catch errors sooner and encourages safer, more predictable code. This naturally leads us to the next topic, where we compare templates with function overloading in similar situations.

Templates Compared with Function Overloading

It is easy to study the rules of overloading and templates. However, it is easy to overlook that together they are one of the keys to elegant and efficient type-safe containers.

– Bjarne Stroustrup

Function overloading is a powerful feature in C++ that is not available in the C programming language. It allows developers to define multiple functions with the same name but different parameter lists. These functions may differ in the number of parameters. They may also differ in the types of parameters they accept. This difference makes code clearer and easier to read.

Function overloading shares certain similarities with C++ templates, which naturally raises the question of why templates are needed when function overloading already exists. Function overloading requires the programmer to explicitly define separate function versions for different data types. Templates, on the other hand, offer a more scalable approach. They provide maintainability by enabling generic programming. This eliminates the need to manually write multiple function implementations. In the following section, we discuss the benefits of using templates over function overloading.

Reduction of Code Duplication

Let’s explore this concept further with an example:

#include <iostream>

#include <string.h>

size_t size_of(int x)

{

return sizeof(x);

}

size_t size_of(double x)

{

return sizeof(x);

}

size_t size_of(const char *str)

{

return strlen(str);

}

int main()

{

std::cout << size_of(10) << std::endl;

std::cout << size_of(4.2) << std::endl;

std::cout << size_of("Hello World!") << std::endl;

return 0;

}Compile and run the program as follows:

$ g++ function_overloading.cpp -o function_overloading

$ ./function_overloadingThe output will be:

4

8

12In this program, we have overloaded a function named size_of(). The same function name is reused for different argument types, namely int, double, and a character string. Each overloaded version implements logic that is appropriate for the corresponding argument type. For integer and double arguments, the built in sizeof operator is used. When the argument is a character string, the standard library function strlen() is used to determine its length.

In function overloading, the function name remains the same from the caller’s perspective. However, the parameter list differs. This allows the compiler to select the correct function based on the argument types. It is also common for the function bodies to differ, as seen in this example.

In contrast, templates often use the same function name. They also employ the same function body. This occurs while allowing the argument types to vary. Function overloading can be used even when the function body is identical. However, templates are preferred in such cases. This preference helps to avoid code duplication.

Stronger Compile Time Type Safety

In addition to reducing redundancy, templates provide stronger type checking compared to function overloading. Consider the following example.

🔗 func_overloading_type_conversion.cpp

#include <iostream>

int foo(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

double foo(double x, double y)

{

return x + y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << foo(10, 20) << std::endl;

std::cout << foo(10.2, 20.3) << std::endl;

std::cout << foo(10, ‘A’) << std::endl;

return 0;

}We have overloaded a function foo() with a pair of integers and with a pair of doubles. Now in the main function, we have first passed two integers to foo(). Next, we passed two doubles to foo(). Finally, we have passed an integer and a character to foo(). Now if you compile and run this program, you will see an output like this:

$ g++ func_overloading_type_conversion.cpp -o func_overloading_type_conversion

$ ./func_overloading_type_conversion

30

30.5

75foo() function has returned 75 as a result of the addition of the characters A and integer 10. Notice that we do not have a version of foo() which accepts an integer and character. However, the compiler didn’t give any error. The input char is implicitly promoted to int. The ASCII value of 'A' is 65. This promotion is done by the compiler. However, this may not necessarily be the intention of the programmer. Let’s rewrite our foo() function as a template function:

🔗 function_template_type_check.cpp

#include <iostream>

template<typename T>

T foo(T x, T y)

{

return x + y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << foo(10, 20) << std::endl;

std::cout << foo(10.2, 20.3) << std::endl;

std::cout << foo(10, 'A') << std::endl;

return 0;

}Now if we compile this program, it will show the following error:

$ g++ function_template_type_check.cpp -o function_template_type_check

function_template_type_check.cpp: In function 'int main()':

function_template_type_check.cpp:13:29: error: no matching function for call to 'foo(int, char)'

std::cout << foo(10, 'A') << std::endl;

^

function_template_type_check.cpp:4:3: note: candidate: template<class T> T foo(T, T)

T foo(T x, T y)

^~~

function_template_type_check.cpp:4:3: note: template argument deduction/substitution failed:

function_template_type_check.cpp:13:29: note: deduced conflicting types for parameter 'T' ('int' and 'char')

std::cout << foo(10, 'A') << std::endl;

^As you can see, the compiler has spotted the mismatch. There is a discrepancy in data types between the function template definition and the argument types passed in the call. So evidently, template functions guarantee to detect accidental wrong parameter passed to it, but function overloading does not.

Macro versus templates

One other programming construct that may feel similar to templates is the macro. At a superficial level, macros and templates appear to address the same fundamental problem: avoiding repetitive code when the same operation needs to work with different inputs. This apparent similarity often leads programmers to ask whether macros can serve as a legitimate alternative to templates. To answer that question, we need to examine how macros actually work and recognize how fundamentally different they are from templates within C++.

A macro is a preprocessor construct identified by a name. Once defined, the macro name may be used anywhere in the source file where preprocessing is performed. Macros may also be defined with parameters, which allows them to be invoked in a function-like manner. This similarity in appearance is purely syntactic and does not imply any form of type awareness or semantic checking.

Macros operate through blind textual substitution. During the compilation pipeline, the preprocessor processes the entire source file first. It expands all macro invocations by replacing them with their corresponding definitions. Once this preprocessing step is complete, the resulting expanded source code is passed to the compiler. At that point, any information about macros has already been lost.

Macros are defined using the #define directive. For example, if the identifier CPP is intended to represent the string literal C PLUS PLUS, it can be defined as follows:

#define CPP "C PLUS PLUS"Every occurrence of CPP in the source file is replaced with "C PLUS PLUS" during preprocessing. This substitution is unconditional, context independent, and occurs before the compiler sees the code.

Macros therefore perform simple textual substitution and can accept arguments of any form. This surface-level flexibility is sometimes mistaken for generic behaviour. In reality, macros have no understanding of types, expressions, or intent. They expand text, leaving interpretation entirely to the compiler.

Templates, by contrast, are a core language feature of C++. They are processed by the compiler, participate directly in the type system, and enforce strong compile-time checking. This fundamental difference means macros cannot substitute for templates, despite superficial similarity.

The following examples demonstrate where macros fall short and why templates are preferred for type-safe generic programming.

#include <iostream>

#define add(x, y) (x + y)

int main()

{

std::cout << add(10, 20) << std::endl;

std::cout << add(4.2, 5.8) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Here, a macro named add() is defined using the preprocessor. Within the main() function, this macro is invoked twice. In the first invocation, both arguments are integer literals. In the second invocation, both arguments are floating-point literals.

In each case, the preprocessor performs a direct textual substitution by replacing the macro invocation with its expanded form. The compiler then evaluates the resulting expressions as ordinary C++ code. Because the expanded expressions are syntactically valid in both cases, the compiler successfully generates executable code. If you compile and run the program, the output will be as follows:

30

10

The add() macro behaves as expected when invoked with a pair of integers. It also produces the correct result when invoked with a pair of floating-point values. This outcome can create the impression that macros are suitable for eliminating repetitive code across different data types.

In reality, this behavior is incidental rather than deliberate. Macros are expanded by the preprocessor, not by the compiler. They are therefore outside the language’s type system and are subject to no type checking, no semantic validation.

The following example demonstrates how this limitation can lead to subtle and unintended errors.

#include <iostream>

#define multiply(x, y) (x * y)

int main()

{

std::cout << multiply(10, 20) << std::endl;

std::cout << multiply(10 + 10, 20 + 20) << std::endl;

return 0;

}In this program, the macro multiply() is defined to compute the product of two values. From the main() function, the macro is invoked twice. In the first invocation, both arguments are integer literals. In the second invocation, each argument is an arithmetic expression. If you compile and run this program, the output will be as follows:

200

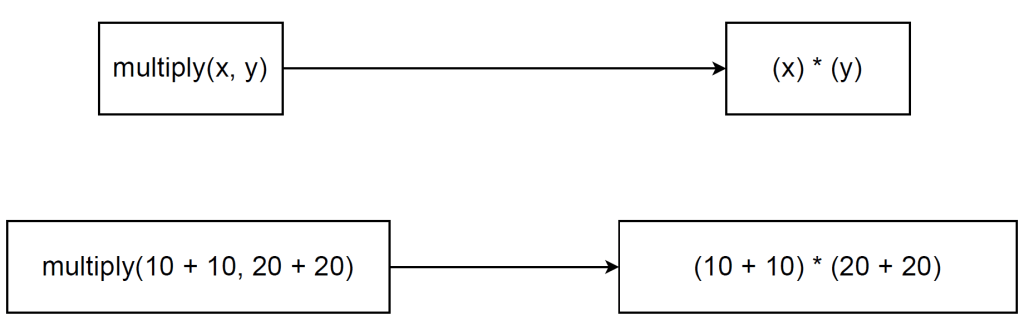

230The output from the first call to multiply() is correct. In the second call, however, we pass two expressions as arguments: 10 + 10 and 20 + 20. The intended computation is (10 + 10) * (20 + 20), which should produce 800. Instead, the program prints 230, which is incorrect.

This happens because macros are expanded through textual substitution. When arguments are supplied to a macro, the preprocessor inserts the argument text into the macro body. It does this without adding any additional parentheses or considering operator precedence. In this case, the call:

Figure 1.2 – Side effect of incorrectly defined macro

To avoid this problem, parameters in the macro definition are embraced in brackets. Let’s have a look at the modified version of our multiply macro:

#include <iostream>

#define multiply(x, y) ((x) * (y))

int main()

{

std::cout << multiply(10, 20) << std::endl;

std::cout << multiply(10 + 10, 20 + 20) << std::endl;

return 0;

}Now, if you compile and run the program, you will see the correct output:

200

800Here’s a pictorial representation of the effect of this modification is as shown next:

Improperly defined macros can therefore introduce subtle and hard to detect bugs into a program. A second drawback of macros is their impact on code size. A macro is expanded by direct textual substitution. Its entire body is inserted at every point where the macro is used. Repeated invocation of the same macro causes duplication. This can lead to a noticeable increase in the size of the generated code.

A third and more fundamental limitation of macros is that they are processed by the preprocessor. The compiler does not process them. As a result, macros are completely outside the compiler’s type system and are subject to no type checking. To illustrate this issue, let us revisit the add() macro in the following example.

#include <iostream>

#define add(x, y) (x + y)

int main()

{

std::cout << add(10, 5.2) << std::endl;

return 0;

}And the following is the output:

15.2In this program, an integer and a double are passed to the add() macro, producing a result of 15.2. From a purely numerical perspective, this result is correct. When the macro is invoked, the arguments are substituted directly into the macro body. The compiler evaluates the resulting expression. It applies implicit type conversion by promoting the integer to a double. This is done before performing the addition.

Although this behavior may seem harmless here, it often fails to match the programmer’s actual intent. The macro might have been written expecting only integer arguments. When a floating-point value slips in accidentally, the macro expands silently. The compiler then applies whatever conversions it chooses, with no check to catch the misuse.

For these reasons, macros fall short for reliable generic programming. They lack type awareness and provide no safeguards against incorrect usage. Templates overcome this by working within the compiler’s type system, enforcing strict compile-time verification. In the next section, we examine function templates in more detail.

Important facts about templates

There are aspects of function templates that need further emphasis. Let’s learn about some unique characteristics of function templates in the following sections.

No Template code generated if not used

The compiler generates no executable code for a template unless the template is actually used in the program. A template serves only as a blueprint for a function or class parameterised by generic types.

Templates use placeholder types rather than concrete data types. Without knowing the actual types, the compiler cannot produce object code from the template definition alone.

Code generation happens only during template instantiation. This is when the compiler substitutes specific types for the generic parameters and compiles the resulting concrete function or class. The following example illustrates this behavior.

🔗 template_code_generation.cpp

#include <iostream>

template<typename T>

T add(T x, T y)

{

return x + y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World" << std::endl;

return 0;

}In this program, a function template named add() is defined. However, the template is never instantiated because it is not invoked anywhere within the main() function. Compile the program and generate the binary executable as shown below:

g++ template_code_generation.cpp -o template_code_generationThe generated binary executable has been named template_code_generation. To verify code generation for the add() function template, use a standard Linux utility. This utility is called strings. Let us examine the output.

$ strings template_code_generation | grep addThe strings utility, when applied to a binary file, prints all human-readable character sequences present in that file. In this case, we passed the binary executable template_code_generation to the strings tool. Then, we searched the output using grep for the string add. No results were returned. This indicates that no symbol or string corresponding to add exists in the binary. This confirms that no code was generated for the add() template. We can now repeat the same process by searching for the string main, as shown below:

$ strings template_code_generation | grep main

__libc_start_mainAs observed, the string main appears in the binary executable, but add does not. This confirms that the compiler generated machine code for main() but produced nothing for the add() template, since the template was never instantiated.

Note: No machine code is generated for function templates unless they are instantiated. A template definition alone triggers no compilation. Code appears only when concrete types are used.

This behaviour differs from ordinary functions. Even unused non-template functions may generate code, depending on compilation and linkage settings. The following example illustrates this difference.

🔗 function_code_generation.cpp

#include <iostream>

int add(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

In this program, a non-template function named add() is defined but not invoked from within the main() function. If we compile the program and then search the binary executable for the string add, we observe the following result:

$ g++ function_code_generation.cpp -o function_code_generation

$ strings function_code_generation | grep -i add

_GLOBAL__sub_I__Z3addii

The add() function appears in the binary executable, though its name is modified by C++ name mangling. Name mangling encodes additional information into function names during compilation. This supports features like function overloading by distinguishing functions with identical names but different parameter lists at link time.

This chapter focuses primarily on function templates as they offer a simpler entry point to template concepts. The core principles (definition, instantiation, and code generation) apply equally to class templates. Class templates receive comprehensive coverage in Chapter 6.

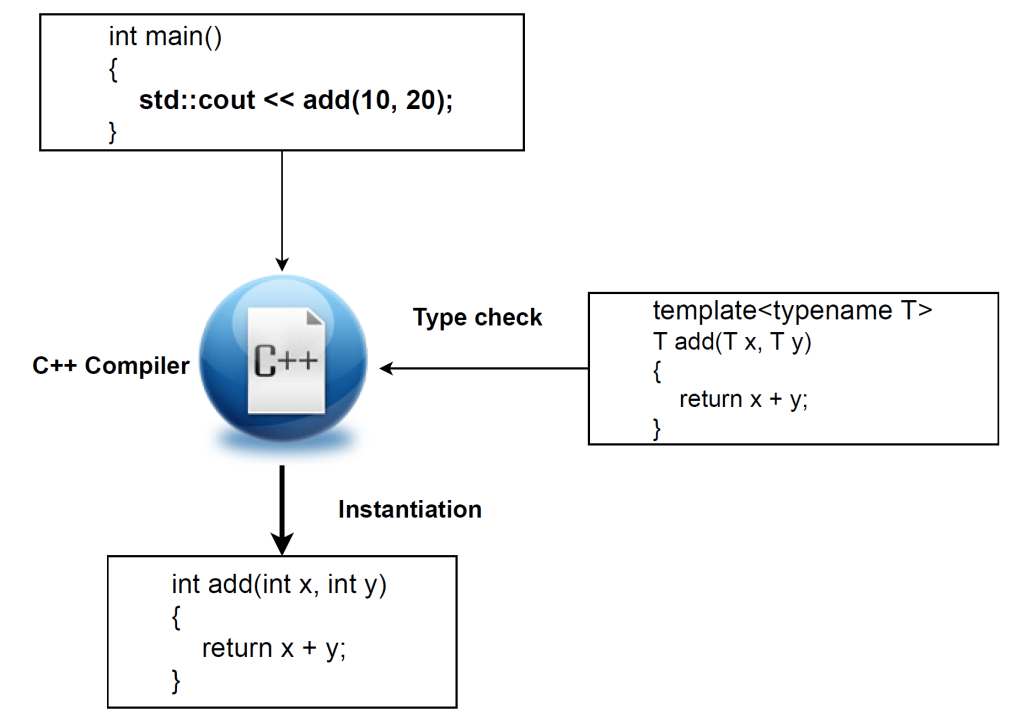

Template instantiation

Templates serve as patterns provided to the compiler. They describe how a function or class should be generated for different data types, without defining concrete implementation. A template by itself produces no executable code. Instead, it specifies the structure that a future function or class will have once actual types are supplied.

When a template is used, the compiler examines the template definition and the argument types at the point of use. If compatible, it generates a concrete version by substituting the generic parameters with actual types. This process is called template instantiation.

The resulting function or class behaves exactly like a manually written one. It follows standard compilation rules and produces ordinary machine code.

The function template add() has been invoked with two integer arguments, as shown in the preceding conceptual model. In response, the compiler instantiates a concrete version of add() with int as the template type parameter.

This instantiated function is equivalent to one a programmer could write manually with integer parameters. There is no functional or structural difference between the compiler-generated version and a hand-written function. Once instantiated, it behaves exactly like any ordinary function in the program.

Semantic Errors Only at Instantiation

The compiler doesn’t performs full semantic or type checking on a template unless it is instantiated. If a template function is defined but never used, the compiler generates no code for it. It reports no errors in its internal logic.

Syntax checking still occurs: Any syntax errors in the template definition are detected at compile time, regardless of instantiation.

Semantic errors appear only during instantiation. Type usage, invalid operations, or incorrect assumptions are checked only when concrete types are supplied, since those checks depend on the actual types used.

#include <iostream>

struct mystruct {

int a;

};

template<typename T>

void foo(T& s)

{

std::cout << s.a << std::endl;

std::cout << s.b << std::endl;

}

int main()

{

struct mystruct s{10};

return 0;

}In this program, mystruct defines an integer member a. The template function foo() accepts a reference to a user-defined type and attempts to print both a and b members. However, main() creates a mystruct object but never calls foo().

$ g++ error_checking_template.cpp -o error_checking_templateCompilation succeeds without errors. The compiler performs no semantic checking on the template body since foo() is never instantiated.

The structure lacks a member named b, a clear programmatic error. Yet the compiler reports nothing. This happens because template body errors are checked only when the template is instantiated through actual use. To verify this, add the following line in main() just before the return statement:

foo(s);And then try compile the program again and you should see the following errors:

$ g++ error_checking_template.cpp -o error_checking_template

error_checking_template.cpp: In instantiation of 'void foo(T&) [with T = mystruct]':

error_checking_template.cpp:18:10: required from here

error_checking_template.cpp:11:20: error: 'struct mystruct' has no member named 'b'

std::cout << s.b << std::endl;Type checking

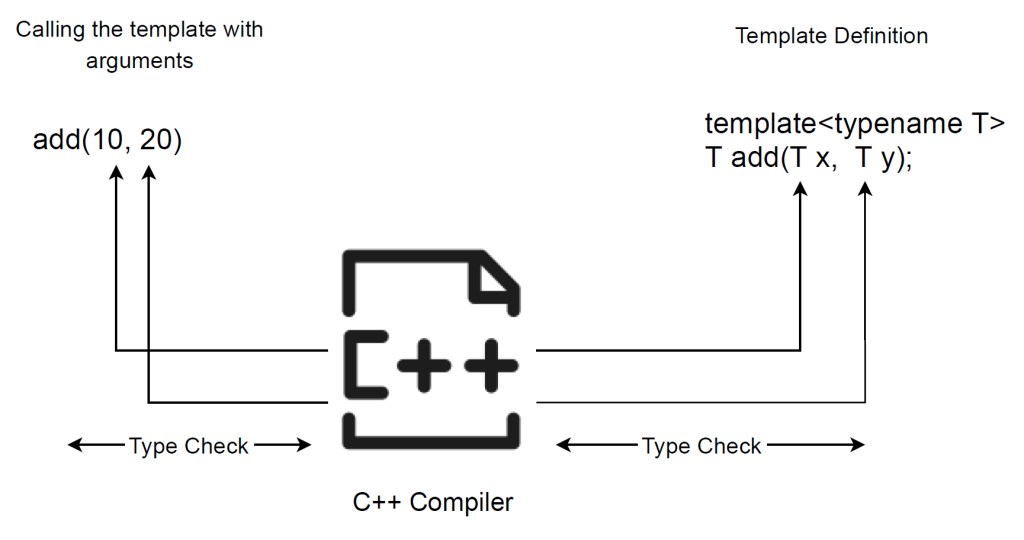

When a template function is invoked, the compiler performs type checking based on the arguments supplied at the call site. It compares these argument types with the template parameters in the definition. If compatible types can be deduced, the compiler instantiates the template and generates an ordinary function with those concrete types.

If deduction fails or the types violate template requirements, compilation fails with an error. This occurs at compile time, before any executable code is produced.

Conceptually, the compiler matches call-site argument types against the template parameter pattern. Successful matching triggers instantiation; mismatch produces a compilation error. The figure below illustrates this model.

Memory usage with templates

It is important to understand that using templates does not reduce memory usage by itself. When a function template is instantiated with different data types, the compiler generates a separate concrete version for each distinct type used. For example, if a function template is instantiated with three different data types, the compiler produces three separate function implementations.

This behavior is no different from manually writing three separate functions, each operating on a different data type. In both cases, the compiler generates three independent blocks of executable code. The memory required to store these functions is effectively the same.

In other words, templates do not introduce additional memory overhead compared to equivalent handwritten code. They primarily reduce source code duplication. This also improves maintainability. However, the generated machine code occupies memory comparable to explicitly implemented alternatives.

Summary

- C++ templates enable generic programming by allowing functions and classes to operate on multiple data types using a single definition.

- Templates reduce source code duplication and improve readability, maintainability, and long-term code health.

- The Standard Template Library (STL) is extensively built using templates, demonstrating their importance in modern C++ programming.

- Function templates provide stronger compile-time type safety by preventing unintended implicit type conversions.

- Compared to function overloading, templates offer a more scalable solution when the same logic applies across multiple data types.

- Unlike macros, which rely on preprocessor-based textual substitution, C++ templates are compiler-checked and type-safe.

- Template code is generated only during template instantiation when concrete types are used; unused templates produce no executable code.

- Syntax errors in templates are detected at compile time, while semantic and type errors are reported only at instantiation.

- Each template instantiation generates a separate concrete implementation, meaning templates provide compile-time polymorphism without additional runtime overhead.

- This chapter establishes the conceptual foundation of C++ templates before introducing template syntax and advanced usage in later chapters.

By now, you should have a clear understanding of what templates achieve and the motivation behind their inclusion in C++. Chapter 2 : Working with Function Templates in C++ dives into function template syntax and practical usage.

Source Code

All the source code for the sample programs shown in this chapter is available in the following GitHub repository.

2 Comments